Michael Delgado of A.G. Geiger Fine Art Books

TEXT ANYA JOHNSON

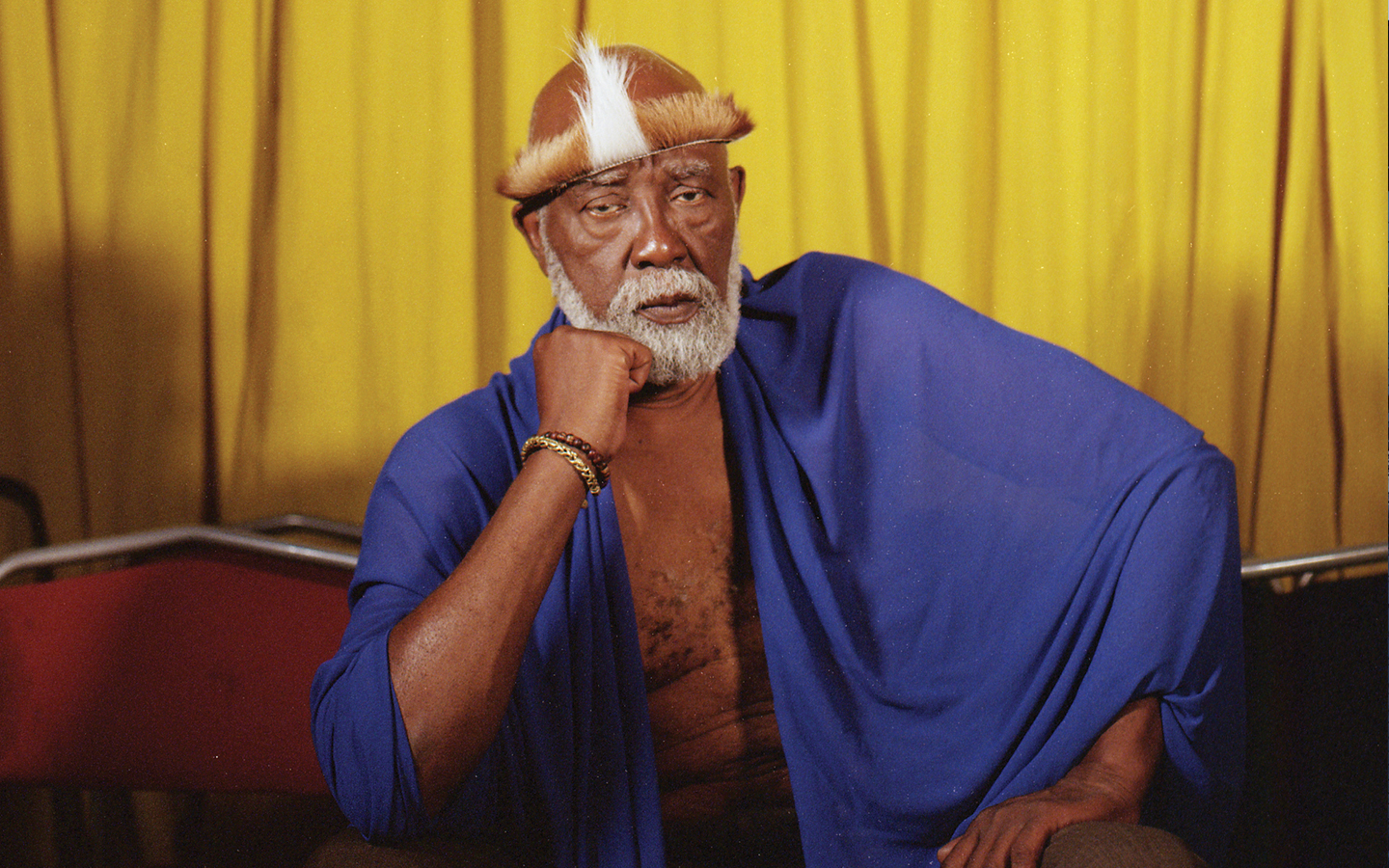

VISUAL ASHLEY GUO

Michael Delgado is compact and laughs easily. Our safe word is “Marlowe”—established in case Delgado becomes uncomfortable with a line of questioning. This sparks some confusion, as Marlowe is also the name of Delgado’s pug. As with any lively meeting, mirth is forecast.

On my first visit to A.G. Geiger Fine Art Books and Press, Chung King Court is overcast and empty. I arrive before Delgado and have some moments alone in the shop; it is smaller than expected, occupying only a third of the boxy space, and lacks pretension. The books have clean faces and strange names, mostly photo collections and monographs. Some jackets are particularly magnetic: a cowboy at dusk wreathed in flames on the cover of Cerro Gordo, or the tawdry, gold-lit motel suite pictured on Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Delgado’s choices, from title selection to the shop facade, reflect his preoccupation with noir. However, there is no fiction here. No graphic novels, no best-sellers, no sci-fi tucked into the back corner. Even Delgado’s favorite author, Raymond Chandler, from whom the name “A.G. Geiger” is lifted, is absent. Instead, the shop is rife with visual dedications to the shifting fiction that is Los Angeles.

When Delgado arrives a few minutes behind me, he is accompanied by Marlowe, whose name, I learn, is another nod to Chandler. Delgado wears a knit cap and long sleeves; it is unusually brisk. When I ask Delgado how he chooses which titles to stock, he says plainly, “The books in the store are the ones I don’t mind people fingering.” We are dealing with a clever man.

More significantly, A.G. Geiger specializes in Los Angeles artists from 1955 to the present day. Later, Delgado explains: “Fifty-five is because it’s sort of a defining moment with Ferus Gallery. Ferus opened around then, and there was a transition from the artists who were more classically trained—Le Brun and those guys, Vincent Price— it changed a lot. After that, it became ‘The CoolSchool’ and the ‘Beat’ things that happened in San Francisco, George Herms and assemblage and Wallace Berman and all that in the early 60s. So, that was a really transforming moment. At the time when Ferus opened, the only contemporary art museum was what is now the Norton Simon. It’s a really formative period for LA art that became internationally recognized.”

The tightly curated collection at A.G. Geiger is one arm of a larger community Delgado means to build. His current focus is a series of weeklyartist podcasts he hosts out of the historic Mayfair Hotel Library Bar. Eventually, Delgado would like to present live casts out of the Mayfair, accompanied by dinner and conversation—in essence, bringing literary salons into the twenty-first century. When I question his idea of community, Delgado clarifies: “When I say ‘community,’ I mean like-minded people who share an affinity for the printed word and want to meet other people like that.” Maybe we’re not looking at an all-inclusive community ideal, but historically, that has never been the point of such gatherings. Delgado’s community is aspirational, and a degree of exclusivity is often central to stirring a social renaissance.

Red lanterns thread through Chung King Court, giving it the appearance of a festive, if sodden, plaza. Delgado lives upstairs. From above, crowded terraces are strung with laundry and other instruments of housekeeping, adding to the neighborhood’s staged aspects. It is almost romantic. Potted palms and two pristine white shirts drying on a line outside of Delgado’s front door are consistent with the scene, while minutely setting him apart.

His apartment is cozy and littered with the debris of an artist. Delgado describes himself as neither precious nor terribly disciplined when it comes to making his own art. There are flower petal assemblages on paper drying by the windows and creased tubes of oil on his workbench. Several large wood panels topped with fiberglass depict a gam of hammerhead sharks circling toward the ocean’s surface. Many of Delgado’s pieces are inspired by classic pulp fiction covers, yet they manage to feel distinctly personal.

Visual art is just one of Delgado’s mediums. “I used to write for LA Weekly,” he tells me. “I was the art-editor person there who wrote the ‘pick of the week.’

After that, I wrote for the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (LAICA). There was LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions) and LAICA— and this was in the early 80’s when you could still get grants and everything for what was known as ‘alternative spaces,’ so they were both artist-run organizations.”

Forty-one years later, LACE is still going strong and Delgado has gone from intern to the Board of Directors. And LAICA’s publication, the Journal, is now housed in the Smithsonian as part of the Archives of American Art.

What’s delightful about Delgado’s progression is his uncalculated pedigree: “I started collecting art books in college, not really realizing that I was collecting books—I just liked them. But as part of my work- study program, you know, to pay the tuition—I was at USC, going to art school [for film]—I was the AV dude. For four years, I was the dude who was showing the Art History visuals during lectures, right, and I saw everything from the course on early Chinese art to the modern survey, to the Baroque-specialized MFA classes. So, four times a week, three times a day, I’m getting inundated with this stuff.”

He also worked the reference desk in the art library and practiced a shrewd method of indexing titles that made him indispensable to patrons. In this way, Delgado was intimately involved in putting together texts for his fellow students’ research. In fact, this may have been his first position as a curator.

A.G. Geiger is a more personalized continuation of this practice. Part storefront, part office, the Chinatown plot acts as the figurehead of Delgado’s developing enterprise. It is a touchstone for artists in a rapidly developing part of LA, and an outpost for the reader who values the hunt for, the heft of, and the physical engagement with bound books. In other words, it is an experience rather than a retail-hub. Delgado voices what every bookseller knows: “The only way you actually sell books these days is to have a community; to have people who are your regulars and believe what you’re doing in the store is cool, and appreciate your curatorial efforts. Because that’s the crazy thing, somebody will come in and look at a book, and then they’ll, you know, get on their phone and put it in your face and say—”

“—Look, I can get this for $20 on Amazon,” I finish the sentence,grimacing.

“And I’ll kick them out of the store,” he counters.

“Do you?”

“Yeah, I’m like ‘fuck you, go buy it on Amazon!’” “Do you actually say it in those words?”

“Yes.”

By the time I leave Delgado’s apartment, it is raining, and tenants scramble to bring in their laundry. The white shirts have gone damp again. Before I say goodbye, I ask what his measure of success has been for A.G. Geiger.

“Well,” he says wryly, “I run the retail operation kind of like a community service, so, keeping the lights on is pretty good.”