Alex Fink

TEXT JACKSON ROCKWELL

VISUAL ALEJANDRO OHLMAIER

Beneath the streets of DTLA’s Skid Row sits a windowless basement workshop, cluttered, but not messy: a commonality among makers at work. The room was dusty and worn-in, reminiscent of an old world atelier. Just out of reach sat a gorgeous vintage archtop, the kind I’d lusted for as a teenager. Countless other instruments were scattered about the room, tucked between an array of exotic tools with names and functions I’ll never know, though Alex Fink can probably use them in his sleep – he made most of them himself.

Alex spends many hours in his shop repairing conventional guitars, but his passion is pushing the boundaries of what the instrument can be. “There are tons of builders that are making really amazing stuff, and it’s really cool,” he explains. “But we’re reaching a point in the guitar community where people are far less married to traditional shapes and styles than they used to be.” Besides experimenting with a guitar’s shape, he also designs instruments with alternate tunings and unconventional stringing patterns, as well as using molds from the Baroque and other periods.

It’s a powerful thing to see one so firmly in their element – so powerful that it’s easy to forget they haven’t always been that person in that setting. Alex explains that “it wasn’t until I was in my first year of music school [at USC]. I brought a guitar to a shop in LA. I won’t mention the name, but I got a really crappy setup done. It was a really bad job. I played it a bit and thought to myself ‘I’m handy enough with a screwdriver to fix this…’”

Whether we consider ourselves handy or not, few of us are comfortable taking a screwdriver to our beloved instruments. It helps that Alex comes from a long line of makers. His father and grandfather were dedicated tinkerers who taught Alex the importance of knowing how to repair and modify the objects in their lives. However, it took some extra-familial motivation to push Alex into the specific field of guitar craftsmanship.

“I had a professor who was a big advocate of making all of our own adjustments. He’s the one that removed the fear of doing my own work. Guitar players are often taught from an early age not to tinker with their instruments – always get someone qualified to do that. But that’s not necessarily true. You can get in there, adjust the neck incrementally, and see what it does. It’s meant to be adjusted. Just don’t go cranking on it.”

A few years later, Alex landed a position at the Gibson showroom in Beverly Hills. They had just cut their budget and lost their guitar tech. “I went in for an ‘interview,’” Alex explained, “and it literally went like this: You play guitar? Yep. You do set-ups? Yep. When can you start? I spent that entire summer going in every day, getting used to different guitars, and moving on to more advanced repairs.”

Alex’s experience at Gibson built a solid foundation of guitar knowledge, but it also opened his eyes to the possibilities of what a guitar could do, if only there was the right tech to set it up. “I started doing mods behind their back. I’d find push-pull pots, which you can pull on to turn into a switch. I’d throw some of those into the Les Pauls they had lying around that I knew no one would be using — ‘this one gets a coil tap. That one gets a phase switch.’ No one even knew.”

The most intriguing thing about great craftsmen is that their maker-mentalities don’t end with their work — the most successful of them build entire lives to suit their fancies, which is exactly what Alex did. Rather than following the well-trodden path many of his fellow music majors adhered to or diving into a corporate lifestyle, Alex discovered a unique yet viable route through life that draws on his strengths and interests. But the path wasn’t always easy, or even obvious.

“One thing I’ve had to go through that was pretty difficult, which happens multiple times in any artist’s life, is this moment of reconciliation with your younger self. ‘Alright 12-year-old to 18-year-old Alex. I know you really wanted to be up on stage, shredding face in front of thousands of screaming people. I know that really meant a lot to you. But that’s not really in the cards right now.’”

It may sound depressing, but in Alex’s mind, it’s a dodged bullet. “I knew deep down that if I did try to pursue music, if I made that my nine-to-five, it’d be a pretty quick road to hating playing the guitar. When I take my guitar out of its case, I don’t want to feel that shitty I-don’t-want-to-get-out-of-bed feeling that comes with a terrible job. I always want to be excited to play.”

Alex was fortunate to come to this realization and make adjustments early in life, but he urges others not to rush into one thing too quickly, especially if they’re young. He poses a question: “How many people do you know that say ‘God, I’m already 25… or 27…. or 30. I’m so old and I still don’t know what to do with my life.’ I think that our perception of our age and where we should be is completely blown out of proportion… I draw a lot of inspiration from my father, who made a very fruitful career in the film business even though he wasn’t on his first movie until he was 34. We all have time. Just try a bunch of things, see what works, and see what doesn’t.”

Though he loves his current work, the journey isn’t over for Alex. He continues to tinker, pushing boundaries and making discoveries as a luthier, as a maker, and as a human being. From the confines of his homely workshop, he sees what works, and what doesn’t, improving his life and the lives of those around him.

You may also like

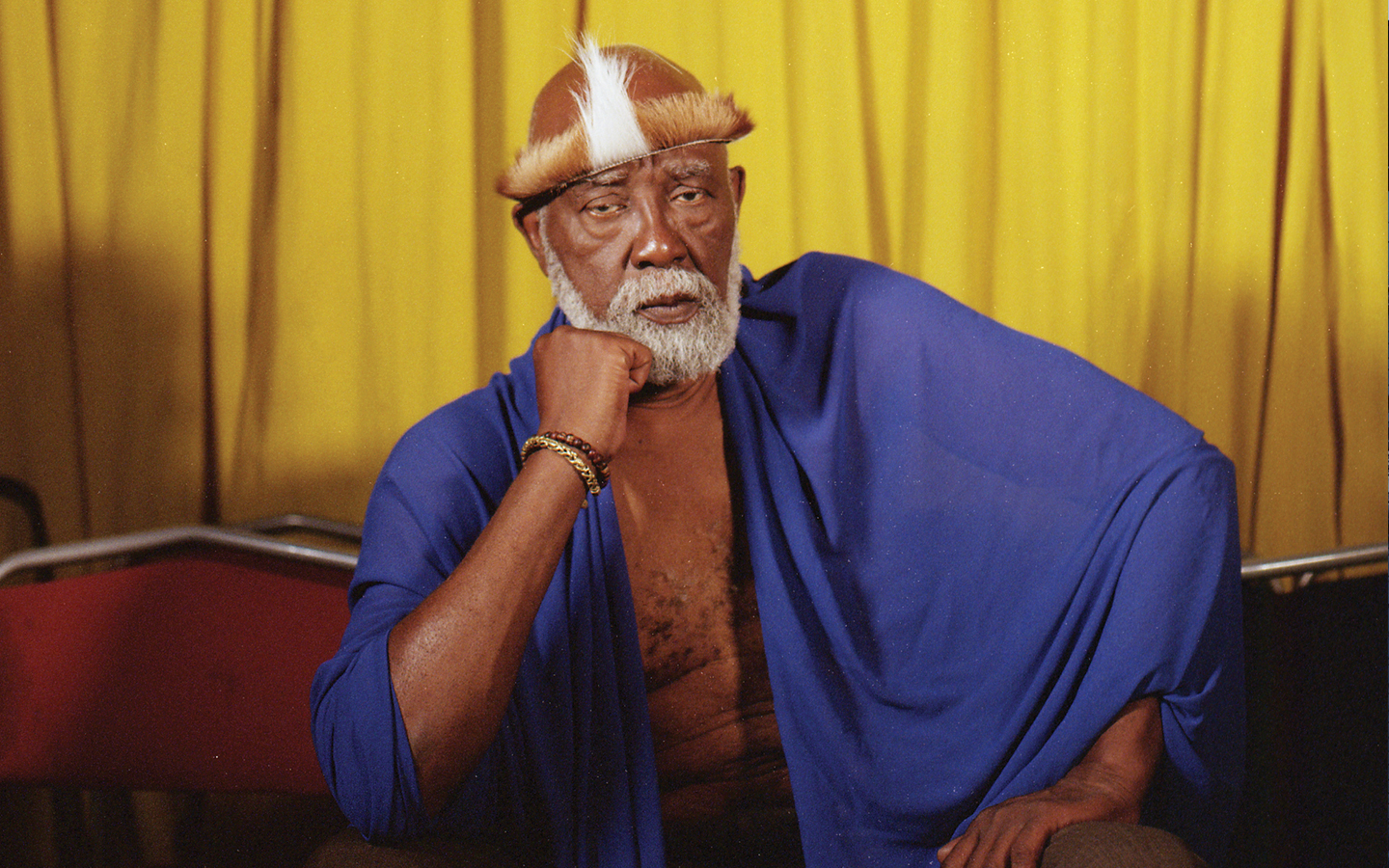

Ben Caldwell

Ben was a founding member of the LA Rebellion, a collective of African-American film students that h

Psolomon Williams

Psolomon Williams could have been anything he wanted to be. Originally interested quantum physics,h

DJ Moonbaby

Angela Jollivette’s childhood dream was to be an orthodontist, which is a far cry from manufacturi