Freedom & Haiti

TEXT AND VISUAL ROWYNN DUMONT

FEATURING JEAN-DANIEL LAFONTANT

For many people, the conceptualization of Freedom could mean a myriad of things. The term is grounded within the establishment of power, power over the right to one’s own actions, feelings, and desires. Freedom is liberation, release and deliverance. It can also suggest that of privilege and self-government. Jacques Lacan, the Parisian intellectual, notates his thoughts towards the meaning of Freedom; in his text, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. For Lacan, there is a fascination between the notion of Freedom or Death. He takes Hegel’s analysis of the Master-Slave Dialectic and its primary concern with how alienation serves in the case of slavery. He states, “Your Freedom or your life! If he (referring to the slave) chooses Freedom, he loses both immediately — if he chooses life, he has life deprived of freedom” (Lacan, 212). Lacan labels this thought process as “lethal” in its indication. It is not so dissimilar from being placed on the blade of a knife’s edge. “Freedom or death” was the cry of the French Revolution. This same essence, a few years later, is echoed to the call of Freedom in the Haitian Revolution, “Live Free or to die!”

The Haitian Revolution itself was a clever orchestration in the establishment of Freedom. To “Live Free or to die” did not mean to only fight physically, but it also meant to create an entire culture, religion, aesthetic, and language around the concept of Freedom. That same idea of Freedom still rings true today amongst the Haitian people. For them, their country has gone through periods of political unrest, continuing into the present time. Last year, I interviewed Jean-Daniel Lafontant on the subject matter of Freedom, Haiti, and Vodou culture.

Jean-Daniel Lafontant was born in 1962 with the gift of clairvoyance. He graduated from the State University of Haiti, INAGHEI School of Management and Diplomacy, and attended the New York Institute of Technology, where he studied marketing. He spent many years in the economic sector of development in Haiti. For a while, he was the head of communications for the Haitian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, broadening his diplomacy and global politics experience. Many things can be said about the career path of Jean-Daniel, but to truly understand who someone is, you must first have an appreciation for who they are to the people around them. Jean-Daniel is a multitude of things, a business professional, a scholar, healer, and father. A man of many-colored hats, however, above all, he is a pillar in his community. He has a deep respect and involvement concerning his countries art and cultural heritage. He is a Vodouvi, a Houngan, and the founding member of the Vodou Temple Na-Ri-VéH. The core of this sacred space is rooted in the tradition of Lakou Djisou and Bwakayiman. As Jean-Daniel states, “I am a Sèvitè: my purpose in life is to serve the divine energies of our dimension, the Lwa, my communities, and the Divine in Mankind.” Jean-Daniel is very much a part of the heart that beats within the cultural lifeblood that resides within Port-au-Prince, Haiti. I was curious to hear his thoughts on Freedom, what it meant to him and to Haiti.

Dumont: Please introduce yourself, tell us a little about your background, what you do, and where you reside?

Lafontant: My name is Jean-Daniel Lafontant. I grew up in Haiti in Port-au-Prince. I grew up in the neighborhood of Poupelard, in the vicinity of the Greater Bel-Air area, which has always been a significant part of Haiti’s culture. It has also been a bastion of resistance and resiliency. My mother is from the north of Haiti, which is historically a very proud side of the country, and I think that in many ways, my spiritual and Vodou inheritance is primarily from that North Side, even though I grew up in Bel Air, I would say that my true family Vodou Heritage comes from the north. I am from a very prominent Lakou, named Jisou or Djisou. Who existed before the Independence of Haiti. They said that Lakou was born in the early 1800s. So this is the city where I’m from, so I am a child. A “Child” means that this is part of my Heritage, my spiritual Heritage. I have taken part in that culture and brought it to Port-au-Prince, where I manage a Vodou Temple created in 1999 and was baptized on January 6, 1999. I am an ordained Vodou priest commonly called a Houngan, and I work these days primarily in the Arts promoting Haiti’s culture, particularly for the Vodou culture.

Dumont: Can you tell us about Temple Narivéh? What place does it hold in your local community? And how are you involved?

Lafontant: The name of the Badji (Vodou Temple) that I founded is located in Bel-Air. It is called Temple Na-Ri-VéH 777. It is more of a community center than a temple. It becomes a temple when there are ceremonies or working of the spiritual world, but people hang out there most of the time. It is a place where people gravitate to when they have problems. The Temple is always a place that gathers the community together and helps them cope with Haiti’s reality of life, which is quite harsh most of the time.

Dumont: What is your idea of Freedom and how does it relate to Vodou and Haiti?

Lafontant: Freedom for me? I would say that Freedom is two words Vodou and Haiti. Okay, for me, this is the true meaning of Freedom. I will start with the Genesis of Vodou, as we know it today; it began in 1791 during the Congress, called the Congress of Bwakayiman. I’ve met a few brothers from the Igbo (African) tradition. Who told me that the word “Bwa kay ayi aman” in their language means to “meet and plan.” So the Congress of Bwakayiman that started in the Summer of 1791 reunited all the kingdoms and nations of Africa. For me, those 54 African nations that we know of, United on a tiny piece of land to declare that they would live free or die. This is the sermon of the Bwakayiman. For me, the first Revolution and the greatest Revolution of the New World, that a group of barefoot slaves, would unite with the few free to get Independence and to abolish the system that was then in place, the design of slavery not Colonialism, but slavery. For me, it’s the greatest symbol of Freedom. And that was made possible [00:39:18] because of two things. First, I mean evidently, the determination of those people was made possible because of two things first Vodou and second Creole. Vodou gives them spirituality that would be under all those African kingdoms whether they are the Kongo kingdom, Dahomey, all the kingdoms of Africa, the Ghanaian kingdoms, all these Nations, those 54 African countries would meet in a place and agree to become one for the first time in history for the sake of living free or dying because this is the true symbol of Haiti. The French Revolution was not the true symbol of the Haitian Revolution. The Moto, the primary symbol, was to “Live Free or to die.” So for me sacrificing your life for Freedom is the greatest tribute. And they actually would sacrifice their life for that Freedom. There are your stories of slaves putting their hands in French cannons, to stop them. So we know the sacrifices made for them to achieve that Independence and for them to be free.

So I think the most significant symbol of Freedom in the world is Haiti. And that would not have been possible without Vodou because Vodou and Creole, as I said, united for the first time. I’m saying 54 African countries because they are all part of this nation that existed in one tiny land. None of them spoke the same language. Each of them came from different cultures and traditions. Because of their diversity, people from the same areas of Africa would not be put together. They were systematically split up so that they would be separated and unable to communicate. So for all those people to unite [00:42:18] in the face of all this division, created for them never to unite, never to speak their own language, never to practice their own religion, and for them to create that language which unified them, which is Creole, and that tradition, that culture and that religion that became one for all of them, which is Vodou. This, for me, is the greatest. These are the greatest Elements of Freedom.

The word Haiti, itself, is the greatest symbol of Freedom.

Dumont: Can you please tell the readers more about your practice as a Houngan and how it relates to the idea of Freedom, in a personal way?

Lafontant: The most extraordinary form of Freedom is Possession. The capacity of someone to let the Spirit Within and allow the Spirit to become one with you. When this happens, you go into a state of total disconnect from the world because you let these energies in. Like the Yin and the Yang, the energies outside and the energies within when they connect you become One, then you are no longer you. You become one with the universe. So this is the state of Possession when you are no longer yourself. You become one with these energies, which is quite often the ancestors’ energy, and then you have a total disconnect with the world in which we live. For me, this is maybe the utmost symbolism of Freedom because you are no longer yourself, and when you come back to yourself, you have that sensation of almost ecstasy. You know who you are in a world, and it is profound. I don’t know, I’m not finding words, but it is like Nirvana. It is a sensation in which you have a sense of profound peace. This is Freedom.

Dumont: Thank you for sharing such a profound and personal answer. Here is the last and most important question of the day, “What do you eat for breakfast in the morning?”

Lafontant: So it’s quite interesting because I thought about that question and I wasn’t sure what I should answer because I live in a different world. Yeah. Yeah. No, I get it. So you have to adapt to the world in which you live. There are two answers, depending on where I am actually.

Dumont: I understand that. I will rephrase the question, “What do you like to eat for breakfast in Haiti versus when you are out of the country?”

Lafontant: Yes, I think it’s essential that I speak about what I eat for breakfast in Haiti because of the tradition of Vodou. I have a set of habits that are part of that tradition. When I wake up generally, the first thing that we do in Haiti, I’m talking about the Good majority of the people, not the minority, the majority we drink, what we call a bitter tea when we wake up. And we do it before we even brush our teeth. So we use different plants depending on the region. So this is my regiment. The first thing that I would do in the morning is drink tea. It’s on the bitter side, and it’s a healing tea also. And a bit later, I would have coffee. I do not drink coffee without sugar, so it’s black coffee and sometimes with cassava or peanut butter; and sometimes avocado. That would be my breakfast. I would say my early breakfast. I would have another breakfast, maybe around 11 am, where I would have made soup, or I don’t know perhaps some Herring and plantains or some other roots, like Yuka. So that would consist of my daily diet in Haiti.

In the US, I would have started the morning with tea. Still, I may skip it and go directly to a coffee and generally with the piece of bread. I have a very simple diet.

Bibliography

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. New Paltz, NY: McPherson, 2004. Print.

Feldstein, Richard, Bruce Fink, and Maire Jaanus. Reading Seminar Xi: Lacan’s Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis : Including the First English Translation of “position of the Unconscious” by Jacques Lacan. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995. PDF.

Interview with Jean-Daniel Lafontant. Conducted by Rowynn Dumont, 27 November 2020 & 19 March 2021.

You may also like

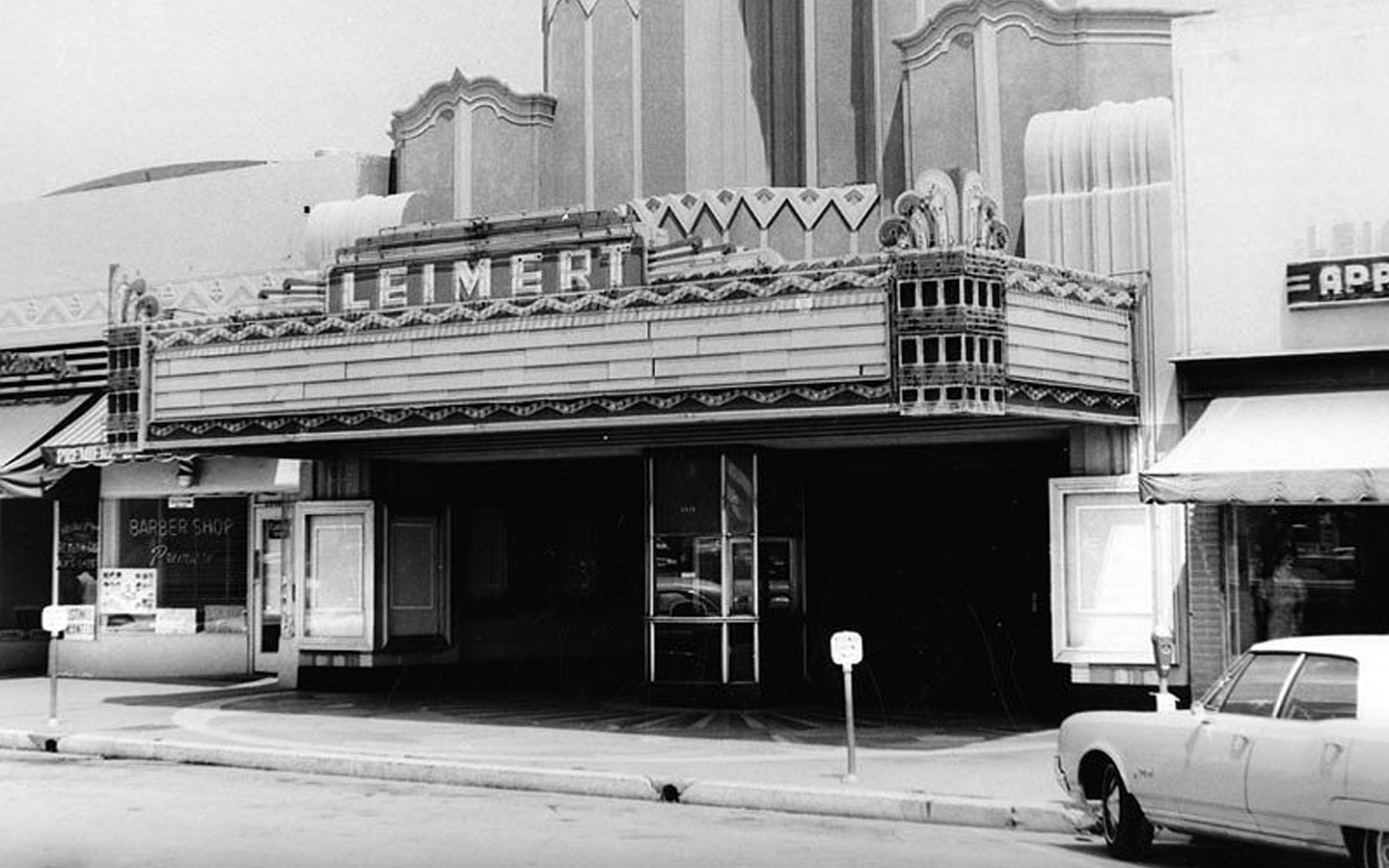

The Vision Theatre

In 2012 the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs completed a $11 million renovation of

Philip Lassiter

Philip is a minister whose religion is music. HIs piano: the pulpit. His horn players: the deacons.

Reverend Gadget

At Left Coast Electric Vehicles, a gorgeous 1947 Ford is waiting for its electric upgrade. “My cli