Harpreet Kaur

TEXT KATE FERGUSON

VISUAL ALEJANDRO OHLMAIER

Harpreet Kaur has been born many times. Her most recent incarnation, as a yoga instructor and an artist, came into this world in 2007, though these labels fail to describe her in full. She embodies the life of a creative in a multi-layered way that defies simple explanation.

Kaur does not shy away from extremes or bold beliefs. She accepts energetic vulnerability, while being clear about the need for boundaries. She offers the distinct truth of her reality, but in the next breath, she admits that she could be unequivocally wrong.

“I hate the process,” she claims, but art has long been an integral part of Kaur’s life; it even catalyzed her journey into yoga after a jarring creative block. Shortly before a promising exhibition which depicts the female form, her work was abruptly pulled. She was crushed, but soon came to realize that the creation of her art was ego-driven.

“Everything was invalidating… I shut down. I couldn’t work anymore.”

Yoga offered a sense of renewal, and it quickly transitioned from a workout into a lifestyle: “It made me feel good. It was a healthy drug. I was dead inside, and it reawakened me.”

Though Kaur’s frustrations with art clearly influenced her beginnings in yoga, the relationship is not a one-way street. The search for deeper meaning through yoga would also inform her art. Kaur’s work is eclectic in form, including painting, illustration, embroidery, knitting, dyed fabric using the Japanese technique of shibori, printmaking, sculpture, ceramics, and jewelry/wearable sculpture. Much of it incorporates lessons learned during her transformations as a yogi, though other themes are also evident.

One theme that consistently appears is the presence, and perhaps more frequently, the absence, of sex and love.

“It’s always been a search for love. I’ve definitely tried to grow to self-love more, but it’s always been for love. Even our drive for success, it’s so other people will love us. It seems like the translation of monetary gains [is] for people to love us. Like if you go in a shop and you have more money to spend, the person that’s helping you will like you more. This whole idea of capitalism depends on us wanting love,” she says.

“I’m painting on shells… the biggest [symbol] of love. Venus stands in a shell; it’s like your vagina: it’s like a clam. If you look at almost all my paintings you’ll see, like, two lips, women with boobs… I recently learned that the transition from ape to man and how we transitioned from fucking from behind to fucking to the front was because initially, the butt was what attracted your mate, but now it’s your boobs… In the animal world, if you’re face-to-face, you want to fight. That’s why violence and sex… it’s a power struggle. Almost all the time. All my work, it’s got to do with this. This union, this existential crisis that I’m constantly trying to fill.”

As a woman, Kaur took to the female form as a natural way to explore these concepts in her art, but she’s aware that her artististic representations would shift if her experience of life were more strongly linked to a male partner. If you’ve seen Kaur’s work, the yearning for that perspective should not be a secret. There are many depictions of snakes, even as she proclaims, “I fucking hate snakes.” She is, of course, aware of the symbolism.

“I always wondered if it was a representation of the penis; you know, maybe I’m obsessed with that. Hindus love snakes. The cobra pose [in yoga] is the hardest for me, because it’s a heart-opener. The [Aboriginal] Australians believe that the rainbow snake is the person who created the world, the god-creator. In dreamtime mythology, the snake is a transformational creature, it sheds its skin and it’s reborn. Like reincarnation. They do that in this lifetime.”

Deep introspection plays a large role in Kaur’s art and personal life, yet she holds an animalistic explanation for almost everything. She knows that self-love is crucial, and that people need other people in a visceral way. She accepts that the feeling of completeness is multi-faceted.

“It’s a crisis I had hoped yoga would fill. Yoga literally means union, it means yoking, and I was, like, okay, I can get this within myself. But you can’t. Because of how we are biologically designed. We are apes, we need social interactions, we need touch, we need to be groomed… We need that essentially for our neurological system. Like if you take a baby and you don’t hold them, their brain develops differently. I think that happens to our brains throughout [our] lifetime, not just as babies.

“The neuroplasticity of our brain is constantly changing and if you go through a period where you lack comfort, affection, stability, it fucks with your head and you change biologically. I think a lot of social ills [could] be sidestepped if we were more aware of it. The fact is that we’re not these ultimate enlightened beings, we’re kind of animals and we need to address all these situations. Respect for one another… being able to support yourself, having a family in whatever form that comes. Taking care of people and having people taking care of you. That is success.”

When Kaur shows us some of her work, she is sure to point out the pieces that she hates. She feels okay about showing these because she thinks they help people to understand the conflict raging within her. “Even when it’s ugly,” she says, “there’s still some beauty in the ugly art.”

She shows us an unfinished piece depicting a transparent woman. Kaur explains that the subject of the painting is protecting herself, yet at the same time, being completely exposed. In a way, this parallels Kaur’s own dualism. In all she does, there lives both edge and vulnerability. As she seeks a balance, this yogi-in-process gives life to both through her art.

You may also like

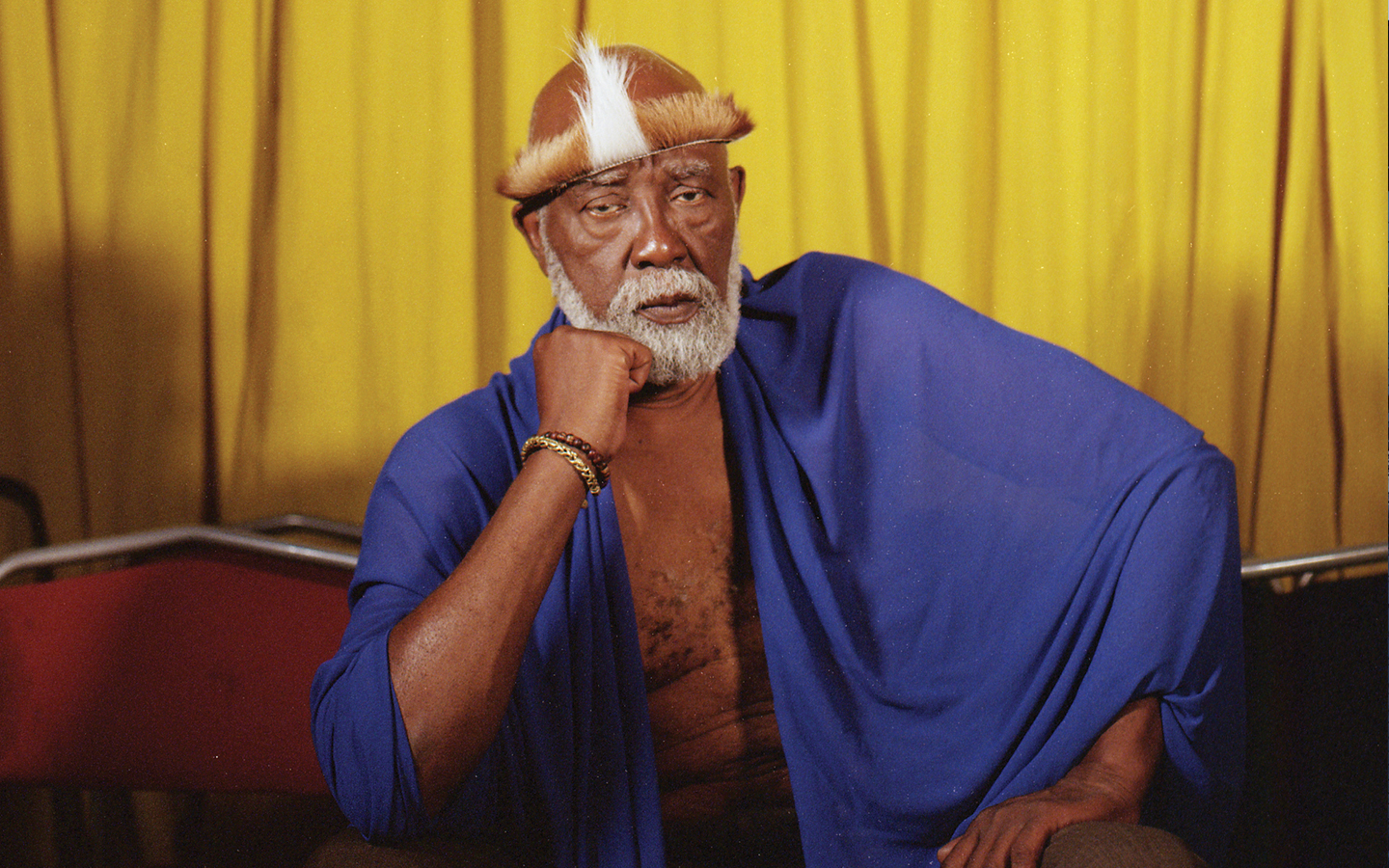

Ben Caldwell

Ben was a founding member of the LA Rebellion, a collective of African-American film students that h