Man With a Parrot

TEXT NICKY LOOMIS

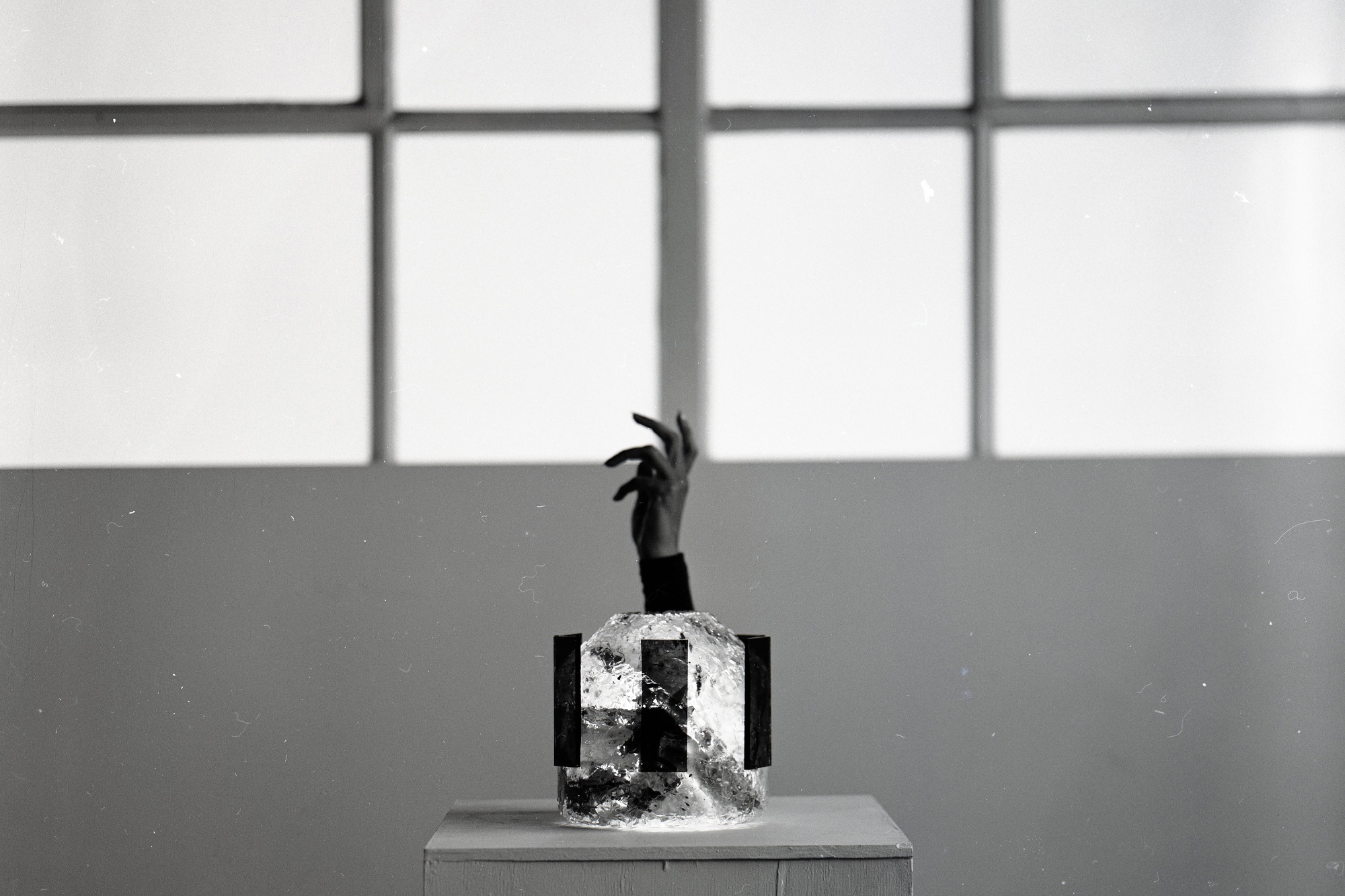

4X5 FILM

CREATIVE DIRECTION FARIDA AMAR

It wasn’t the kind of town to question, especially not in winter. Rather, it was the kind of town that let you into its secrets if you didn’t look at them as such. Yesterday, the woman had seen three fat bunnies hop around the Kitzbuhel pharmacy. The pharmacist dropped a few pills on the ground as he counted her ration out, almost as though he was testing them (the animals, not the pills) to see if they’d eat the white capsules. It came as no surprise that they would not.

“They only like cough syrup,” the pharmacist had clarified, and she did not question further.

That same week, she saw a goldfish frozen in the water of an abandoned toilet on the side of the road.

Inside the empty bar, three children played the violin for dulled coins. The woman sat on the bar stool, back to them, sipping her red wine. It was the dead of winter in this strange village and her plans had fallen through.

When the man walked in, she initially took no notice of the small, blue parrot perched on his shoulder.

It wasn’t the parrot that stood out in the end, if she thought about those first few moments, which she often did, always when she was alone, elsewhere, further in time, and never in conversation. He had a smell distinctive to his soul (the man, not the parrot), like a festive candle burning in a church wet with mold. His head smelled of a rotting orange in mulled altar wine—she was sure if she sifted through his long silver hair she’d find clove studs embedded in his scalp. It was intoxicating, that scent, if only because she knew she’d never be able to get to the bottom of it.

Wine gone, another ordered. The man waited to talk. That she remembered.

“Do you have brandy, vodka?” He spoke in English but with that tortured drawl she had grown used to in these parts.

“Sir? This is a bar.”

“And gin.”

He looked at the man and as he did, the parrot hopped onto the counter and turned its head sideways as if to say, silly barkeep.

“But do you have them in that order?”

“Sir, if you are looking to get pissed I suggest the forest cognac. Some people never return from it.”

“Like death,” the man said, drawing out the last word, singing it, mocking it, a cadenza: Like… deathhh.

The woman felt the barkeep looking to her for some kind of verbal support. She offered none.

“I’d like a brandy first, a vodka second, a gin third, and a forest cognac fourth, but you can serve them at the same time, so I can look at them.”

The woman made eye contact with the man and something in her must have been given away: she could almost feel it being pulled out of her, a thread of some memory she would never be able to access.

“She’ll have the same.”

She looked at him in negotiation and settled with, “Does your bird have a name?”

“Bartleby,” the man said. “Tell her, Bartleby.”

I would prefer not to! I would prefer not to! The bird sang, bobbing its head maniacally.

They both laughed. She felt his hand on her leg but looked down and it was gone.

“I found him at the zoo,” the man said and did not elaborate.

“And he doesn’t get cold, wandering around in the snow with you?”

“Every time I ask him if he’d like to stay home, he reiterates his position.”

“What if you ask him if he wants to go out?”

“But I don’t ask him that, you see.”

The barkeep returned with eight glasses lined up neatly on a carving board. There were wet pine needles strewn around the drinks as if to say, fresh.

“Right. Good. Thank you, barman.”

The drinks were served neat and were arranged in the right order. She picked up the brandy.

“Where I come from, we don’t clink until they are empty,” the man said.

“And where is that?”

“Hmm?” he asked, downing the brandy.

“Where you come from?” she said.

“Let’s pretend those kinds of questions don’t matter.”

“I don’t ever want to go home,” she said, downing hers.

“Before we drink the next one, tell me something you’ve never told anyone.”

The woman cradled the glass of vodka between her hands and stared into it like it was a candle warming her face. The parrot walked over to her and nestled its head against one of her hands.

“Every day I take the ski lift planning to jump off and today was supposed to be the day I actually did it.”

“There’s always tomorrow,” the man said.

“I suppose.” The dullness of tomorrow disappointed her. She reached out to try and pet Bartleby but he hopped sideways out of her reach.

“My turn. I’ve pretended to know how to swim my entire life.”

“So you don’t go swimming?”

“I do go swimming. Only, I’m pretending, see.” He clapped his hands together and spread them into the air like he was showing her whatever was in between them.

“So, then, you can swim.”

“If swimming is standing in water then I can swim.”

She downed the vodka. She heard the man mumble something and felt a sharp pain in her temples as he did. The parrot climbed back up the man’s arm and onto its usual perch.

“How would you kill me, if you had to?” she asked. It was sensual, her question, although she couldn’t grasp why.

“Slowly,” he said without taking a beat. “The opposite of the ski lift approach. And you, me?”

“Simple,” she said, still holding the empty glass, her eyes peering into its emptiness like an oracle. “I’d throw you in the lake.” They both smiled.

“So you are ready to die?” he asked.

She took a long pause and held the gin to her lips. “Are you?” she asked. She wanted to taste him.

“I asked you first.”

“It’s never been anything but yes.”

“Well then,” he said, slugging his gin. “So it shall be. Tonight, we agree to let the other kill us, but only if we ever run into each other again.”

“You’d be too easy to find. There are only so many men with parrots on their shoulders.”

“Tell you what. We’ll do a practice round tonight. We’ll finish these drinks and walk in opposite directions. In an hour’s time, we try to find one another—whoever finds the other first, kills them as they see fit.”

She pictured them in the bar bathroom, pulling each other’s hair, nails scraping skin.

“Two more forest cognacs, please,” the man ordered.

The barkeep hesitated. “But you haven’t drunk the first yet.”

The woman nodded to the barkeep to bring them over. It was her way of saying, game on.

“Salut,” the man said to the woman.

“Salut,” the woman said to the man.

They each downed the forest cognacs and ate some of the pine needles for good measure, taking turns making the garbled throat sounds that released as the liquid continued to burn. When the last round arrived, they both drank fast without speaking. They clinked glasses.

Outside, snow fell in that soft, beautiful way that she could still picture all these years later. It was almost like love, the snow, shrouding her shadow like a bride’s veil.

“On the count of three, we split up,” he said. “I go this way, you go that.”

She didn’t want to leave. She wanted to follow him home. Sleep in his bed. Let him keep asking her questions.

“Can we hug?” she asked. “In case we never run into each other again.”

He took her into his arms and pulled her to his chest. The parrot climbed on top of her head and sifted through her hair with its beak. She wondered if the bird could smell the geranium oil in her hair, the oil she had rubbed into her scalp that morning, embalming herself. She could feel their hearts in rhythm as they pressed against each other. They each held on a little longer before the parrot hopped back onto his shoulder and the moment was lost.

“One,” the man said, starting to walk away.

“Two,” the woman said, letting go of his hands.

“Three,” they said together, turning away from each other, both turning around once to smile, once again to wave, and once again to find the other until they couldn’t, until the other was gone.

You may also like

Prepare This Place For Bed

These bees in my mouth: oily, waxy, powerful—one flew into my mother’s mouth at a family picnic

The Carrier

The girl placed the metal bombilla straw in her mouth and took another sip. As the warm liquid snake

The Symposium of Drowning

There is no greater crowd pleaser than a pretty dead girl, especially the drowned variety. You know