Watts Towers

TEXT FARIDA AMAR

“To see the beauty of nature and understand the principles. That’s what Sam, Simon Rodia did. Sam will rank not just in our century, but rank with the sculptors of all history.” − R. Buckminster Fuller

Some of the most extreme and least explained actions of mad geniuses (who are later lovingly referred to as visionaries) are forever cherished as beautiful moments in human history. The Watts Towers of Simon Rodia, commonly referred to as simply the Watts Towers, are one of these moments, and more specifically, they are an epic collection of seventeen interconnected steel sculptures covered with mortar, glass, and tile, still standing with dramatic intention in the South Los Angeles.

Simon Rodia purchased a triangle-shaped piece of land on 107th Street in 1921, and got to work right away. He obsessively perfected his masterpiece “Nuestro Pueblo” for thirty-three years, using only his bare hands nine simple tools. Now please keep in mind, Simon was only 4′ 11”…and he used a window washer’s belt and buckle to build the tallest of his towers… which is 99 ½ feet high; that structure is now recognized as the longest slender reinforced concrete column in the world. Simon Rodia’s work is now celebrated as one of the greatest examples of outsider art and naïve art.

Sabato Simon Rodia (1875-1965) was an Italian immigrant construction worker and tile mason. He followed his brother Ricardo to Pennsylvania in 1895 at the age of 15 and stayed there until his brother died in a mining explosion. He then moved to Seattle, Washington, where he married Lucia Ucci in 1902. They then moved to Oakland, where Rodia’s three children were born. While in Oakland, Rodia worked as a laborer and brick layer, helping build University of California, Berkeley. Lucia officially divorced Rodia (who had became an alcoholic and hot-tempered) in 1912. Following his divorce, he moved to El Paso, Texas where he remarried a woman named Benita, then moved with her to Long Beach to live with his brother, Tony. Benita and Rodia divorced in 1920 (probably also because of the alcohol) and he remarried a woman named Carmen. They settled together in Watts in 1920. He worked in rock quarries and railroad camps as a construction worker during the day and moonlighted as an artist devoting all of his nighttime hours to the Watts Towers. It is said that Rodia began the building of his towers in order to stop drinking, which would explain his obsession with constructing them. His paranoid neighbors thought he was building some kind of insane radio tower. Rodia didn’t seem to mind.

Rodia began each tower with steel rebar, concrete, and wire mesh. He then spent countless hours over three decades decorating each tower with found objects. In order to appreciate the Watts Towers, your mind must be free to dream and able to grasp what does not yet exist and what is not expected to be seen. While many of his neighbors were of the opinion that he had completely lost his mind, the children that lived on his street would often bring him objects to help. Some of the details you will observe when you visit the towers include embedded glass soft drink and milk of magnesia bottles from the 1930s, broken shards of ceramic tiles and pottery, seashells, figurines, mirrors, and rocks. Rodia would walk alongside the Pacific Electric Railway right-of-way from Watts all the way to Wilmington in search of scrap material, a distance of nearly 20 miles. It has been said that the way in which he arranged these objects was not predetermined. Rodia preferred to work on instinct, finding beautiful shapes and patterns as they arrived naturally. In a way, the whole structure behaves as a kind of time capsule.

Rodia signed his work with an imprint of his work tools and his initials “S.R.” in the concrete of his great masterwork. And in 1955 at the age of 75, he quitclaimed his property to a neighbor, Louis Sauceda and left, tired of battling with the City of Los Angeles for permits. There are some rumors that he may have also left after a fall from one of the towers where he was unable to move for two days until a ten-year-old girl found him lying on the ground. Rodia moved to Martinez, California to be with his sister Nicoletta and never returned. In his absence, Louis then sold the property to another neighbor, Joseph Montoya, for $500 or less. Montoya, like many of his neighbors, had no idea the value of the Towers, and reportedly planned on tearing them down to build a taco stand on the property. While under their ownership the towers were left unsupervised and were broken into and vandalized. In 1956, a fire started by illegal fireworks ruined the small house Rodia built on the property and the Department of Building and Safety ordered that the Watts Towers be demolished.

In 1959, William Cartwright, a film editor from USC, and Nicholas King purchased the Towers from Mr. Montoya by paying him everything they had in their pockets, $20 in cash, plus the promise to pay thousands more in the future. The two men, plus their architect friend, Edward Farrell, appealed to the court in a 16 day hearing to save the Watts Towers. Bill & Nick also founded The Committee for Simon Rodia’s Towers in Watts, a group of concerned citizens who collected signatures and raised money to save the towers from demolition with an engineering “stress” or “load” test, designed by Bud Goldstone. The crane was unable to topple or even shift the Towers with the forces applied, and the tests concluded when the crane experienced mechanical failure. The stress test registered 10,000lbs. The towers are anchored less than 2 feet into the ground, and have been noted in architectural textbooks to have changed the way some structures are designed for stability and endurance. This extraordinary fight to save the Towers became one of the most successful efforts to preserve a historical landmark in the city of Los Angeles. Eventually the Watts community began to consider the Watts Towers to be a part of their heritage and called upon the new owners to create what is now the Watts Towers Arts Center.

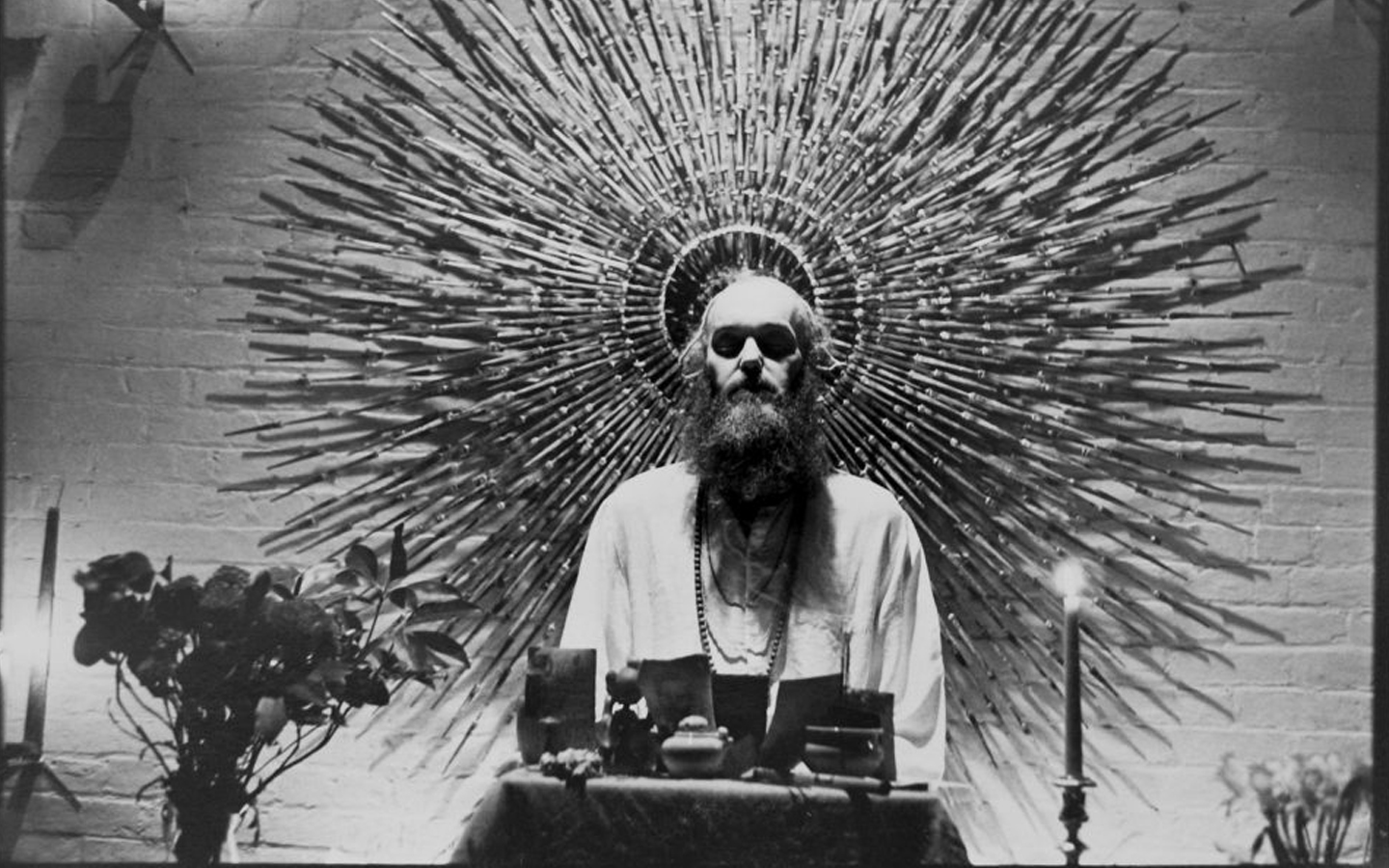

The Simon Rodia Continuation High School in Watts is named after the towers creator. A photograph of Simon Rodia is included on the cover of the Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released in 1967. The Watts Towers are considered one of Southern California’s most culturally significant public artifacts. They are one of nine folk art sites listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and were designated a National Historic Landmark in 1990. In February 2011, LACMA received a grant from the James Irvine Foundation to scientifically assess and report on the condition of the Watts Towers, to preserve the undisturbed structural integrity and composition of the aging work of art.