Al Struckus House

DESIGNED BY BRUCE GOFF, 1982

TEXT ANTHONY CARFELLO

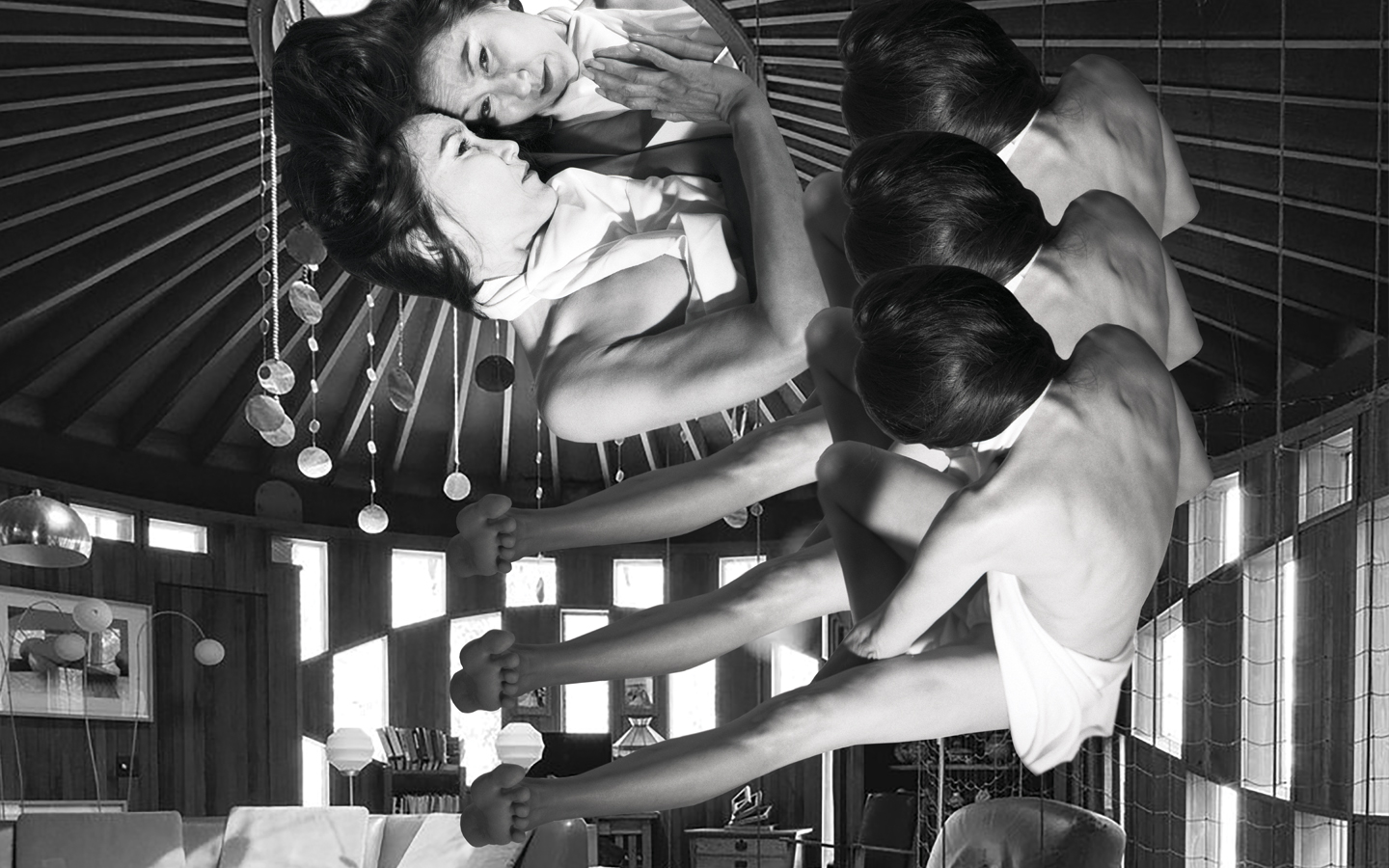

VISUAL MILANA BURDETTE

The Struckus House is a multi-story yurt adorned with silver medallions. It’s a Native Californian religious vision. The house is a four-eyed prehistoric insect, breathing ever so softly. It’s the central cathedral in a medieval Hobbit village. Or is it an H.G. Wells novel set in the West Valley? An acid trip in the forest made structural? Perhaps a redwood time machine sent back from the future by Angelenos in the year 3265?

There is no more difficult piece of residential architecture in the region to describe via comparison than the Struckus House (1982)—it is different from any common notion of domestic space on the planet. It offers an important reminder for Los Angeles.

In a succinct rant about the freedoms of this city, BLDGBLOG author Geoff Manaugh declares, “No matter what you do in L.A., your behavior is appropriate … Los Angeles has no assumed correct mode of use.” Examples follow of one character type belonging as much as another: “You can watch Cops all day or you can be a porn star or you can be a Caltech physicist.” In a spread-out city defined by private space, it’s inferred that this unofficial civic credo takes physical form in the many housing vernaculars, from Mission Revival casitas to French Norman chateaus to Cliff May atomic ranches to Faux-talian mansions to DTLA artist lofts. All intermixed and each promising a unique lifestyle on the resident’s terms.

However, viewed alongside the city’s truly genre-breaking constructions (the A-list celebrities such as R.M. Schindler’s back-to-the-land Kings Road House or Charles and Ray Eames’ consummate professional Case Study No. 8, the Meryl Streep of houses), these styled LA homesteads are revealed to be just like the wannabe actors; spatial versions of believing in the Hollywood myth that says “you’re special, unlike anyone who’s ever moved to Southern California.” Manaugh clarifies, however, “[Los Angeles] says, no one loves you; you’re the least important person in the room; get over it. What matters is what you do there.” And the city’s best architecture reflects the same unpresuming ethos—risk and experimentation first, audience later, if ever.

Bruce Goff never moved to LA. Born in Alton, Kansas, in 1904, his career began in Tulsa, Oklahoma, after his father apprenticed him to a local firm at age twelve. Frank Lloyd Wright

and Louis Sullivan provided early mentorship as Goff designed work around the Midwest before becoming chair of the architecture department at the University of Oklahoma in 1947. Influenced by early modern music—from Maurice Ravel’s Jeux d’eau (1901) to Claude De-bussy, whose

records he played while teaching—Goff would champion an improvisational approach to architecture. Designing was a responsive, organic process more akin to jazz riffing than pre-packaging a product—an especially bold position in the era of the standardized International Style. After being forced out of the school for being queer in 1955, he set up his office in Wright’s only skyscraper, Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, where his highly inventive practice produced radically different results, building after building. Of 500 projects (147 of which were built), what he did in Los Angeles—the Struckus House—was his last, completed posthumously in 1994.

In our current era of branding, where developers and decorators hire cloned influencers to post identical photos in endlessly similar environments, it’s refreshing to compare Goff’s Bachman House (1948) in Chicago and see that it looks almost nothing like his John Frank House (1955) in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, or his Durst-Gee House in Houston (1958). Intrigued by new ideas rather than existing trends or even his own habits, Goff understood there were many faces to architecture.

To form the Struckus House—a four-story tower of California redwood cladding, beige stucco, and glass—six vertical cylinders are bundled together and interlocked, producing a Spirograph floor plan. Designed for an engineer, woodworker, and art collector in possession of a small 50 x 100-foot lot on Canoga Avenue, across from the Woodland Hills Country Club, the house rises from a landscape of pine, bamboo, and saguaro cactus to display its bulbous Plexiglas windows. Behind them, a single spiraling staircase ascends inside a twelve-foot-diameter silo, weaving together an interior space experienced vertically and horizontally at once, with an open lounging area, overlooks behind cargo netting instead of railings, and shaded canopies. Sixty wood beam rafters encircle an oculus strung with hanging garlands of reflective metal—suggesting the Pantheon wearing earrings—that illuminates the principal twenty-four-foot-diameter trunk and its spaces below, including a fourth-story living room, a third-level bedroom, multi-colored, tiled bathrooms (both of which cut away at curves to permit a free-flowing interior), a paneled first-floor kitchen, and an understated dining area.

“The creative architect must be aware of subjecting his works to a ‘personal style’ or a ‘trademark,’” wrote Goff, “each of his works deserves to become its own form and style.”

One needs only to pass through the centrally pivoting entry door to the Struckus House to begin to see this personal challenge in practice. Dozens upon dozens of quarter-inch wooden strips ring around a stunning abstract-bird-feathers-meets-flat-tened-Tiffany-lamp stained-glass composition stretching at least a yard wide. There are no other doors inside save for the bathrooms.

Any architect is responding to site, but Goff spent his life pushing structural site-specificity into having a life of its own—to be more musical—reacting to atmosphere, to his own drafting process, and in particular, to his clients. “Bruce always [became] his client,’’ said the architect’s longtime friend Joe Price. ‘’It was almost like speaking to a mirror.” Designing was an expression of space as a “continuous present”—borrowing from Gertrude Stein—in which the outer shell and interior, the materials, and the inhabitants all intertwine in ongoing harmony and create something absolutely new.

“The whole point,” said Al Struckus, who began communicating with Goff after seeing his work in an issue of Vogue, “is the free flow of the interior space.” The San Fernando Valley bachelor broke ground just before the architect’s death, constructing the house himself over the course of twelve years with the guidance of Albuquerque-based architect (and Goff’s occasional project assistant) Bart Prince. “The layout is so open … that privacy between two or more people would be almost impossible,” Struckus told the Los Angeles Times in 1988 while living in the yet-to-be-completed house. In the spirit of Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, the retiree single-mindedly finished all of the house’s hundreds of details because he felt absolutely that he must. Goff’s mandate that spaces be self-expressive and self-determining became Struckus’s own, no matter the financial hurdles, building department prohibitions, neighbor complaints, or time. Analogous to Rodia suddenly giving up the deed to his house and life’s work on E. 107th Street upon completion, Struckus, too, found that it was the journey of realizing this piece of architecture more than the destination—he passed away mere months after total completion in 1994.

While the next owners—a Getty-affiliated married couple—have remained dedicated stewards of the house since 1998, and while Goff’s other local building, the Googie-Shinto Pavilion for Japanese Art at the LA County Museum of Art (1978, completed 1988), continues to be the most dynamic part of the Miracle Mile campus by far, Los Angeles architecture on the whole has moved in radically boring directions since the Struckus House was on the drafting boards.

What do we see around the city today? Software-generated, corner-cutting, profit-driven Home Depot kit assemblages that leave the effervescent Struckus House looking on like a disappointed parent. The definition of uninspired. Arguments that a need to quickly build housing in a crisis contradict with the unaffordable prices of these “boxes with little holes,” in Goff’s terms.

We have come so far from any concept of inventiveness and autonomy with the design of our domiciles that we barely remember it was once possible. And that history is not found only out in suburban sprawl or among the wealthy (who’ve actually produced some of the worst architecture). From the political progressives who pooled resources to build mid-century architect Gregory Ain’s compact Avenel Cooperative in Silver Lake to the dreamscape of Mid-City’s St. Elmo Village to the Mutual Housing Association in Crestwood Hills, innovative residences produced by their residents, like Al Struckus, have been one of LA’s best forms of Manaugh’s doing.

He writes, “Southern California is where you can actually do what you want to do; you can just relax and be ridiculous.” Yet our proof, like Charles Lummis’s El Alisal or the Mosaic Tile House in Venice, is from previous generations. Nowadays, we’re not able to try anything anymore. Property is too expensive, and housing costs are inflated to the point that we feel lucky to even have a roof—especially in a city with nearly 60,000 experiencing homelessness. We therefore live where we’re told, even if inside drywall blocks smugly painted in grey with neon trim. Landlords forbid creativity. Developers charge extra for curves. Suggestions such as accessory dwelling units—the “granny flats” built in backyards—end up half-hearted investments rather than any place of experimentation.

We forget about all the unconventional examples of taking ownership over space from the past, as well as the practical ones still visible, like the freely repurposed and reoriented front yards of East LA. Instead, we’re left with the Tiny House movement and its DIY-themed marketing that doesn’t seem to produce anything but off-the-shelf tool sheds (and when someone in LA took decisive action to give those away as shelter for people living under the 110 Freeway, the city took them!).

The Struckus House’s flamboyance is a reminder of what now seems impossible—that imaginative Angelenos have figured out ways of incorporating visionary and unorthodox thinking into their homes before and can do so again, no matter the time, the real estate market, the zoning restrictions, or dominant assumptions. Goff’s last offering is a monument to the fact that it doesn’t have to be like this.