The Salk Institute

DESIGNED BY LOUIS KAHN, 1963

TEXT FARIDA AMAR

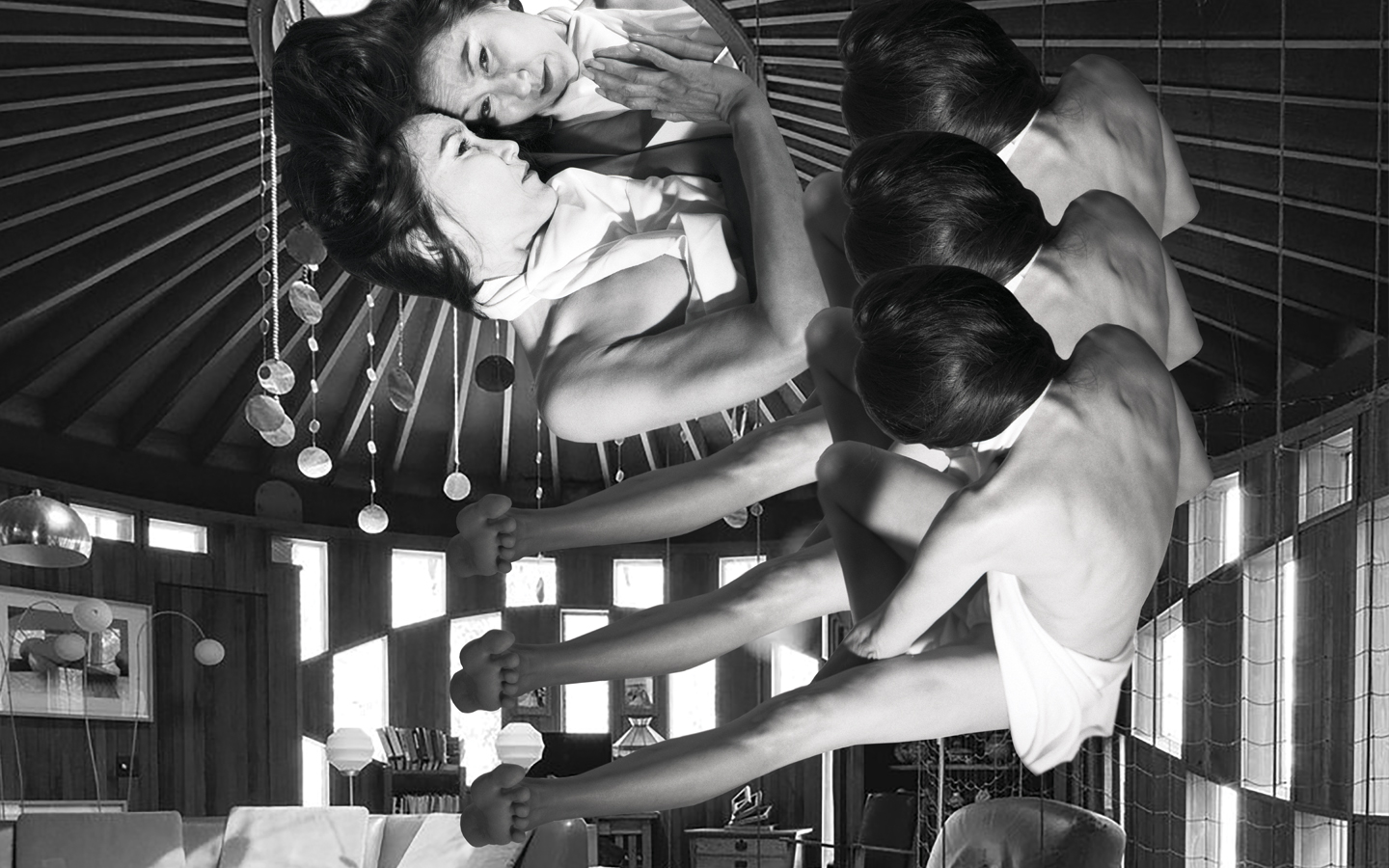

VISUAL SHAUN LANG

If you are a concrete square, but deep down you’ve always known you’re really a circle, you may actually just be a Louis Kahn building.

Tall thin rectangles with long diagonal shadows, overlapping flat lines falling into the abyss of gaping hollow hexagons, circle windows, triangle windows, shattered light crashing down on what could have been a floor but is somehow instead just another ceiling. Louis Kahn’s work is confident. Aggressively slicing into landscapes and sight lines; Kahn is entirely unapologetic about his use of raw materials and sharp geometries. Using natural light to tear open boundaries where you’d expect them to throw their weight and providing the gift of unexpected, mind-bending accessibility from heavy solids such as concrete and brick.

When you first see the Kahn’s work, you feel oddly proud of what he had achieved although you’ve probably never met him and he’s already dead. You find yourself staring at a screen, or a book of his work, or an article like this one with your stupid jaw on the floor, drooling and yet empowered with the spirit of bold confidence he thoughtfully embedded into every crevice of his legacy. Louis Kahn turns us all into confident, drooling appreciators of life. I have the feeling Kahn never made a mistake and that everything you see, even the things you hate, were designed for you to see and for you to hate and are therefore working precisely as intended. Caribou by Odessa begins to play and wherever he now rests amongst architecture’s pantheon of dead geniuses; Kahn knows and now you too know that deep down, we’re all just biological vessels serving as mediums for an intangible spiritual realm, reflecting shadow and light through repeating hollow patterns of negative space contained within the unnatural exoskeleton of our hardened square lives.

Art and science are Siamese twins and both Jonas Salk and Louis Kahn knew this. The symbiotic relationship between the two cannot be removed; without art we would not nurture our instincts to imagine the intangible and without science we would not seek the discovery of their truths. Together art and science have performed the most awkward 30,000-year-long-ish talent show of recorded human history. And although Art and Science sometimes forget the steps and fall out of sync, the passion and determination behind their dance gives each generation of visionary thinkers the confidence to express our most bizarre curiosities regarding the unknown, and to discover, capture and measure our observations and findings. This balance of Art and Science is found in every inch of The Salk Institute and its story begins with the collaborative relationship between scientist Jonas Salk and architect Louis Kahn.

“I speculated on the astronauts and their view of the earth, describing the earth as a marble, blue and green and rose. And looking to it, somehow Paris disappeared, Rome disappeared. Things disappeared that were made by man, but somehow Beethoven didn’t disappear. The Fifth Symphony couldn’t disappear. To my mind. Somebody else, it could be something else. But it simply brought out the very essence of spirit that guides you to be you, or express yourself. And the Fifth Symphony came out, I never thought of it before. Toccata and Fugue came forth. And not Paris, which is made by a whole conglomeration of circumstantial things which are only incompleteness, if you stop to think of it. The plans made that adjust themselves, one way or another, does not still present itself as being that which is a place which is called the gravitational place for people to meet people. Does that make sense? … And then I thought, the question is, I thought also, that wonder came back and that things like knowledge disappeared. You really didn’t want to know so much but the wonder about it, as though you have seen it for the first time. That’s really quite remarkable. You are seeing it for the first time.” Louis Kahn from Louis I. Kahn in Conversation: Interviews with John W. Cook and Heinrich Klotz, 1969-70.

Jonas, who was best known for discovering the first safe and effective polio vaccine, commissioned Louis to design The Salk Institute in 1957. Louis, even then, was arguably the most significant architect of the late 20th Century. Jonas was a man who knew the scientific value of inspiration and that it could be found in every part of life, starting with the design of the environment in which you work. Jonas asked Louis to build him an institute for science “worthy of a visit by Picasso.” In response, Louis built what can only be described as a ceremonial ground for Science to dance with Art. Louis cut straight into the landandscape, inviting nature to walk right in the front door, or in this case through the central plaza. His bold use of clean symmetrical lines, staggered concrete buildings towering over wide open implementations of negative space, as his Modernist heart was want to do, appear to be holding a moment of silence for the sky and sea, the falling of the sun and the rising of the moon, for the last six decades.

The Salk Institute first opened its doors in 1963 with financial support from the National Foundation/March of Dimes. Twenty-ish years later, a young Dr. Tom Albright was first invited to visit as a prospective employee. Having just completed his graduate studies at Princeton University’s interdepartmental program in Psychology and Neuroscience, Albright received a call three years into a four-year post doctoral fellowship at Princeton’s Physiology of Vision Laboratory which looked at how the brain encodes visual information. “Of course I knew who Jonas Salk was, but I didn’t know what the Salk Institute was so I did a little research and realized it was almost brand new. There was something about California, moving West, that really appealed to me. It seemed like a sharp contrast to New Jersey. I came out for a job interview, the guy who was chairing the search committee was Simon LeVay who was also a vision scientist at the time. We had dinner and I came in the next day to meet with a bunch of people including a guy named Francis Crick. How old was I? I was thirty-one and I met Francis Crick and I thought, yeah there is something unusual about this.”

Tom moved to California and began arranging his 1,200 square foot laboratory on the 5th floor. “People have different kinds of reactions to this building, I love this building. And I loved it from day one. I’ve always had an interest in architecture and I embraced the idea of working and spending a good part of my life in this building.” The Salk was focused on molecular and cellular neuroscience, and it was Francis Crick who stepped in and showed support for the development of Tom’s research which introduced systems neuroscience to the institute.

Tom explained to me that it is impossible to really understand how we see if we are focused on studying a person’s reaction to an individual stimulus. We don’t see features in isolation. “A sensory stimulus doesn’t entirely determine your perceptual experience. Your perceptual experience is informed by many things including other stuff that happens to be in your visual field, things that you’ve seen before, things you know to be true about the world, what you’re expecting to see. What I wanted to do was study how those other factors influence your perceptual experience and then be able to identify neuronal signals that were correlated with that perceptual experience. So, we did that. It went incredibly well.”

“ In physical order, every grain of sand is the right size, the right color, the right place. The right weight. One of each. There is nothing you can refute in the way of physical order. That’s a mistake. Even an explosion is a manifestation of order. ”

LOUIS KAHN IN AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN W. COOK AND HEINRICH KLOTZ, 1969

Today, The Salk Institute continues to pioneer explorations on how we see and how we exist. Currently, Salk scientists are focused on developing plants to tackle climate change, identifying strategies to conquer cancer, and working to uncover the mysteries of Alzheimer’s for effective interventions, just to name a few. Fred H. Gage, current President of the Salk Institute, explains, “These endeavors are the product of dedicated and passionate people pursuing scientific research in the glass, metal and concrete ‘cathedral to science’ that we call home, regardless of the season.” The wonderment of life, the desire to be, and to come into being, were of great interest to Kahn throughout his life as both an architect and educator. His respect for the ability to respond to the universe itself and to serve as a vessel for others by designing cultural institutes that inspired contemplation and respected not only their location, but also their intended use, was no doubt why Kahn and Salk worked so well together.

The Salk was originally planned to have four parallel buildings and two gardens on the North and South ends. Jonas Salk and Louis Kahn realized that two smaller courtyards would divide the institute, creating a group that preferred one and a second group that preferred the other and therefore dividing the culture itself in two as well. Therefore, if you visit Kahn’s masterpiece today you will see the result of their final decision to build two six-story buildings rather than four, fashioned of concrete accented with teak, positioned parallel along the boundaries of the property. Each shelters an inner row of angular semi-detached office structures that face each other across a single travertine courtyard which holds no plants whatsoever. Instead of a garden, a channel of water is carved into the travertine, bisecting the outdoor space and providing a sense of symmetry and balance. The elevation of the ground offers you the perspective that this little stream of water is pouring directly into the Pacific Ocean and in some small amazing way, you have the power to walk on the whole ocean, or jump over it with little effort. The use of monochromatic materials on both buildings and the floor of the courtyard aligned with the horizon creates a static composition following a rule of thirds; automatically pulling one’s gaze to focus on the sky and sea rather than the property. The birds in the sky, the smell of salt in the air and the flow of the sea breeze is the perfect recipe for a serene, yet bold freedom; here, it is without question that Louis Kahn’s strong, silent-type vibe and unique approach to Modernism took on a direct rebellion against Brutalism; simultaneously validating the classic design principle of form following function.

Jonathan Salk, psychiatrist and the youngest son of Jonas Salk, commented on the relationship between Louis Kahn and his father in a speech he gave at the 2015 Design Futures Council Leadership Summit on Technology & Applied Innovation, “Their relationship began around 1959 when my father went to Kahn to ask him about how one goes about choosing an architect. My father wanted to build, to create, a new and different kind of institution, and he knew he would need the right kind of building to house it. When they met, they immediately understood one another. They both knew that science and art and intellect and spirit are all connected. My father wanted to build an institution that reflected, studied and enacted that. Kahn was thrilled to have a client who thought on such terms. In retrospect, I would say that they both understood something fundamental – that buildings reflect and create and influence the nature of the institution they are built to house.

I remember Kahn’s face, scarred and bright with life and creativity. I remember a model of a study tower on our breakfast table. With spaces between the floors so that light could flow into the laboratories. I remember my father showing me plans of the monastery at Assisi, talking about the colonnades where people could walk and contemplate and discuss higher things and subjects. And how he wanted the Institute to have the same feel. I remember discussions of nine-foot-high spaces to supply gas, water, and air conditioning to the floors below. I even recall trying to join in the conversation by joking about 9-foot tall plumbers and electricians. I also remember some larger decisions being discussed. Something about interstitial spaces and something about courtyards.”

KAHN ON SALK: “He sees the arts as being grown from an inspiration within us the inspiration to live, the inspiration to express, the inspiration to question, the inspiration to learn…they are inspirations within us from which I would say the institutions of man are derived.”

SALK ON KAHN: “There is a unity to all this, as is revealed by the way in which Mr. Kahn and I have interacted in order to create a building of concrete that has all of the aspects of a living organism with a capacity to grow, change and evolve.”

And so the dance between Science and Art began on the 27 acres of land overlooking the Pacific Ocean in La Jolla, California. And so it continues to inspire the work being done by Dr. Tom Albright and others every day for the past sixty-two years. The Salk is where studies and experiments addressing some of the greatest concerns regarding the fundamentals of life in both tangible and measurable work are being conducted in laboratories alongside the intangible work being done in their minds and spirits. As its first director, Salk said, “The Salk Institute is a curious place, not easily understood, and the reason for it is that this is a place in the process of creation. It is being created and is engaged in studies of creation. We cannot be certain what will happen here, but we can be certain it will contribute to the welfare and understanding of man.” May this dance always exist, may it bring us limitless possibilities for achievement, and may we invent solutions that will outlive us all.