Screaming in Past Tense

TEXT ARJUN RAY

VISUAL TYLER HUBBY

The story of Los Angeles is far too large to ever be fully told. The city and its surrounding metropolitan areas fade seamlessly into the West, East and North—any land not bounded by the Pacific Ocean. For a metropolis of this scale, a person can hardly be faulted for being drawn to the most obvious, attention-getting landmarks when exploring the history of the place. The aging palm trees, Watts Tower, the Hollywood Sign, and the tall buildings of Downtown. But besides the gilded, the tall, and the expansive landmarks of Los Angeles—far below street level—there are ghosts haunting small and unassuming buildings, basements, and urban wreckage. Ghosts of places and people who once asserted themselves as a potent cultural countercurrent in the grimy streets of old Los Angeles. We’re talking, of course, about the Los Angeles punk scene, one of the most important regional punk scenes in the United States, whose tendrils have threaded themselves forward through the annals of history and touched everything from pop music and art to fashion and mainstream culture.

SPECTRAL SONIC SPACES

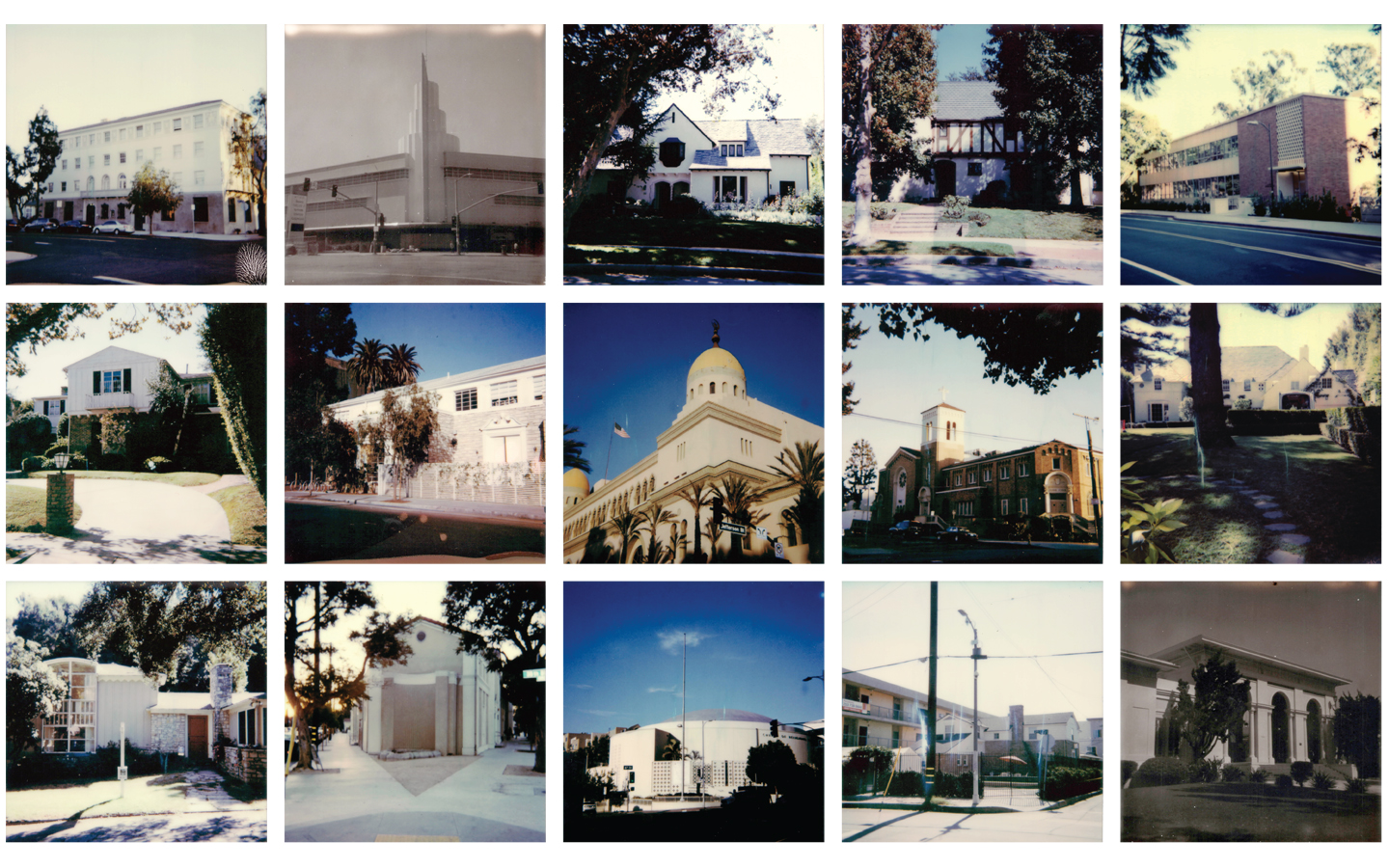

In order to look at the history of punk rock in Los Angeles, specifically the nascent period between the late 70s and early 80s, we have to explore all of the now-defunct spaces where it first took hold. The stories of this scene are written in the architecture, but they cannot be found in the blueprints. They are written in the specifics of squalor. Holes in low ceilings and walls, layers upon layers of graffiti now mostly covered up, broken glass, dried blood. Every single one of these places is now dead, and the stories that unfolded within them have been either been forgotten or elevated to the point of elegy. The truth was that these were the spaces that kids could go to see music that was widely unacceptable in society. Punk was a war against the excess of the 70s and a return to the stripped-down, vital and nasty roots of rock and roll. Punk was also a major act of war against the inherent forced chillness of Los Angeles. In these ways and more, affiliating yourself with punk back in those early days meant declaring yourself a social pariah. These kids needed private spaces to coalesce, build, destroy, and live the way they wanted.

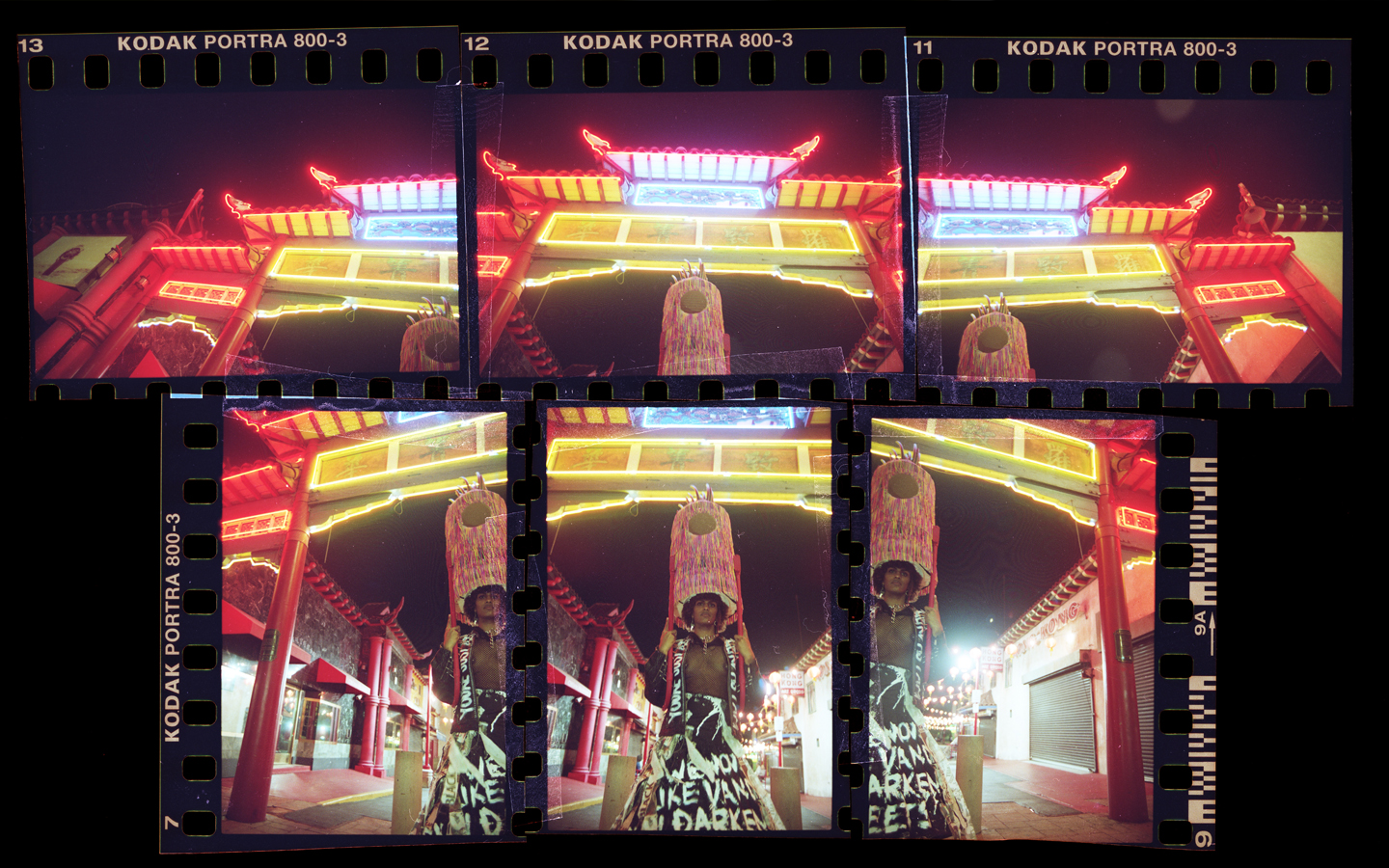

Let’s throw out the idea of safe spaces for a second and distill the concept down to necessary spaces. Underground spaces are often the necessary spaces, without which a scene cannot exist. For such a space, you need electrical power, some kind of enclosure, maybe a bathroom, and not much else. This meant that the punk spaces in Los Angeles ranged from dingy, semi-legal basements to extra rooms in Chinese restaurants, as was the case at Madame Wong’s and the Hong Kong in Chinatown. The Masque was one of the most prolific such venues and was the first actual punk club in Los Angeles, situated in the basement of an infamous Hollywood porn theater. Down the street from the Masque, an apartment building called the Canterbury housed a fully anarchic amalgamation of freaks, outcasts, and actual criminals. Many kids living there met each other years before they became known for being in bands like the Go-Go’s, X, the Bags, Black Flag, and the Germs. These spaces provided relief from societal expectations and suffocating norms, while at the same time tying rivalries amongst scene enclaves to physical locations.

Esther Wong was the owner of Madame Wong’s, and she was known for hand-picking artists to play her venue by listening to their demo tapes. For whatever reason, she disliked punk bands, especially female-fronted ones, favoring less aggressive new wave acts. This drove many of the punk bands to play Hong Kong restaurant instead, which was down the street. At one point, members of Castration Squad, a bombastic all-female punk act influenced by the radical femininst SCUM Manifesto, featuring Alice Bag and others, tricked their way into playing a set at Madame Wong’s by giving Esther a demo from another band.

Across the 7th Street Bridge and over the Los Angeles River, the primary Chicano East LA punk scene rivaled the one in Downtown. East LA punk remained largely separate from Hollywood punk, save for a few attempts at cohesion between the scenes, and overall could be described as steeped in Chicano identity, and grimier and grittier than Hollywood. Bands like the Plugz, the Brat, the Zeros, and Los Illegals helped established East LA punk. The Bags were one of the few bands who had solid footing on both sides of the river. These bands all found a home in Club Vex, which would host their shows every Thursday night. Eventually, the bands from East LA were given chances to play across the river in Downtown, but only once more established Hollywood punk bands like X vouched for them.

Out of these early days came bands like the Go-Gos, who would go on to become double platinum-selling pop artists, bands like the Bags and the Germs, who took punk to its visceral edge to open the door for the evolution of punk into hardcore punk, and X, who became the bard folk heros of the scene, transcending genre labels. Without these spaces, none of this could have been realized, and now, every single one of theses spaces is gone; bought out, condemned, or destroyed.

REVOLUTION OR DEATH

If you live your life above the surface, you’ll only maybe hear about these spaces once they are dead and eulogized. And maybe that’s the way it should be. There is no test like the test of time, and the vital, innovative period of rock and roll has no claim to be any more of a blip on the radar than jazz, baroque, or musique concrète. But for the majority of my life, and the life of many of you readers, rock and roll has been ever-present, giving the illusion of permanence over several generations of listeners. One thing that I’ve always lamented, as someone who spent their teen years in the 90s, is that my generation was never rewarded with a revolution in rock music like the 60s, 70s, and 80s had produced. Yes, in the 90s there was grunge, and it permeated the radio waves along with lesser imitators for half a decade, but unlike the decades before, my generation never coalesced into a rock and roll countercurrent strong enough to revolt against the previous thing.

In this case, the thing to upend would have been punk rock—an expansive title for a panoply of genres, subgenres, and musical evolutions. And after grunge, the story got worse. It’s weak to sit around and complain, and I do not intend to protest or lend maudlin interpretations to history. But history is showing us what it is showing us, and objectively, rock music never really recovered. Following the historic marriage of rock music to radio airwaves, we saw minor evolutions from the punk idiom in new wave, alternative rock, indie rock, the “The” bands, post-punk revival, and then literal radio silence. What I noticed first was a tendency toward nostalgia, where music movements defined themselves more by their retro-sonic aesthetic than by anything truly new that was being brought to the table. After many revivals, the death of music television, and the death of music radio, we have finally come to reside in an era where streaming services account for the vast majority of music consumption. And the numbers are there, clear as day, for anyone to see.

According to Spotify, the last bastions of popular rock music are in the scant “indie rock” categories, which contain such banal selections as Imagine Dragons and Maroon 5, and not much more. Not only has the category of “indie rock” devolved to the point of utter meaninglessness, what qualifies for a rock band is simply containing members who may at some point in their career, in some song, somewhere, play the bass, guitar, drums, and sing, simultaneously. MC5 these guys are not.

I’m not saying we should care qualitatively about the music that makes it onto pop radio. But pop music has always absorbed the most salable and innovative tendencies from fertile underground movements and transformed and mollified these aesthetics into product, producing indirect indicators of a vital underground. Pop music eschewing nearly all elements of rock and roll is the symptom, not the disease. Every time the aesthetics and ideological trappings of rock and roll bubble up into the zeitgeist, you get long-haired lawyers, new age bankers, and other signs of cultural morbidity. Those folks still tapped into the originating live wire push have always been revolting, pushing subculture back into territory fraught with danger, sex, and excitement. Or at least, that has been the expectation up until now.

PROGRESS?

The conditions required for subculture to thrive are usually at odds with urban planning. By definition, counterculture pushes in the opposite direction from that prescribed by societal monoliths and instruments of power, thriving in the uncontrolled fringes of civilization. But there is something markedly different about cities in America these days, a powerful homogenizing force that clamors for dense, expensive housing and tech industry ingress, making life unaffordable for anyone not yoked into the rat race. The urban neglect that provided the romantic squalor for LA punk to exist in the late 70s has been replaced with revitalization projects and gentrification. Five-story condos built of cheap shit materials and rented out for exorbitant prices have invaded the landscape in cities across the country, and those living on the edge of society find themselves squeezed out. In a modern LA, punk as we know it would never have happened. The important exception to this would be the East LA punk scene, which still manages to throw backyard shows on a regular basis, even in the face of rampant gentrification.

In 2016, tragedy struck in a DIY venue called the Ghost Ship in Oakland CA when a fire ripped through the venue, killing 36 people. The deaths sent reverberations through the underground scene across the country, and city officials also took notice. All of a sudden, it became much harder to keep semi-legal underground spaces open as cities did whatever they could to address the apparent danger of such spaces existing within their borders. Many of us in cities around the country have noticed the effect as DIY venues shut down and nothing springs up to fill the void. The house basements, dive bars, and warehouses that have continued to be a home for underground music have come under scrutiny, either because of their misunderstood potential for danger, or because they sit on land that has become attractive for development.

Is rock music in a period of stagnation and diminishment? Can the underground punk scene survive without physical spaces to house it? More importantly, what kind of a city will Los Angeles be if all of its fringes are ironed out, and all of its working class, starving artists, rebels, troublemakers, and malcontents are pushed out? The answer may not be found simply by building better neighborhoods, or investing in short-term strategies like subsidized housing and rent control. Given enough time, none of these buffers seem to stand in the way of the unchecked development that is transforming once vital cities into soulless, insanely overpriced clones of San Francisco. Whether or not rock and roll is past its productive period, there will be yet another countercurrent that upends an uncomfortable cultural nadir for something more vibrant, whether it be through music, art, ideation, or politics. These movements still need a few walls, a roof, a place to piss—a space to call home.