Sheets Under Siege

THE SCOTTISH RITE MASONIC TEMPLE AND THE ERASURE OF LOS ANGELES HISTORY

TEXT JEFF LEAVITT

VISUAL NIKO SONNBERGER

THE SPACE

Upon reaching the center of the space, a visitor will be met by pure white drywall panels on all sides, a high steel-beam-and-panel ceiling coated in a grey, spray-applied fire-resistive material overhead, and a gleaming polished concrete floor underfoot. All of these glamorous architectural appointments bask in the 5,000 Kelvin glow of pure white fluorescent tubing. This space is the epitome of utility, efficiency, and sterility—perfect for any industrial chemical lab, machine shop, motor pool, or aircraft hanger. Unfortunately, this is the schema that the Marciano Art Foundation has chosen for its newest art museum. In an attempt to “foster synergy between the historic building, contemporary art, and the urban environment,” wHY—the design team responsible for Los Angeles Scottish Rite Temple’s transformation from Masonic sanctuary to contemporary art space—has successfully rendered the building’s interior bereft of nearly all its previous historical and cultural identity.

The gallery space itself does indeed allow for a high level of flexibility, which was desirous for Kulapat Yantrasast, the creative director of wHY’s design team, who stated that “flexibility has widely become the keyword for Twenty-First Century museums as boundaries surrounding exhibition, art, and institution are constantly being pushed and even erased. I like to take a position on flexibility with an attitude—open, confident spaces with qualities and characters need exist before any flex happens in them.” Yantrasast’s design does result in an adaptable space in which a plethora of artistic endeavors could be carried out, but should the space be subservient to the art? Should site-specificity and history bow out in favor of adaptive wall real estate? Should the “white cube” paradigm set by the Museum of Modern Art in the 1930s prevail in all cases regardless of the building’s cultural context? Should we allow the sterile museum hellscape, as so pertinently identified decades ago by Brian O’Doherry, remain the only viable option? Should Los Angeles be home to yet another art museum that invites its visitors to gaze into the soulless void of dull and tired gallery design, beckoning us once more unto the breach? I don’t think so.

A LITTLE HISTORY

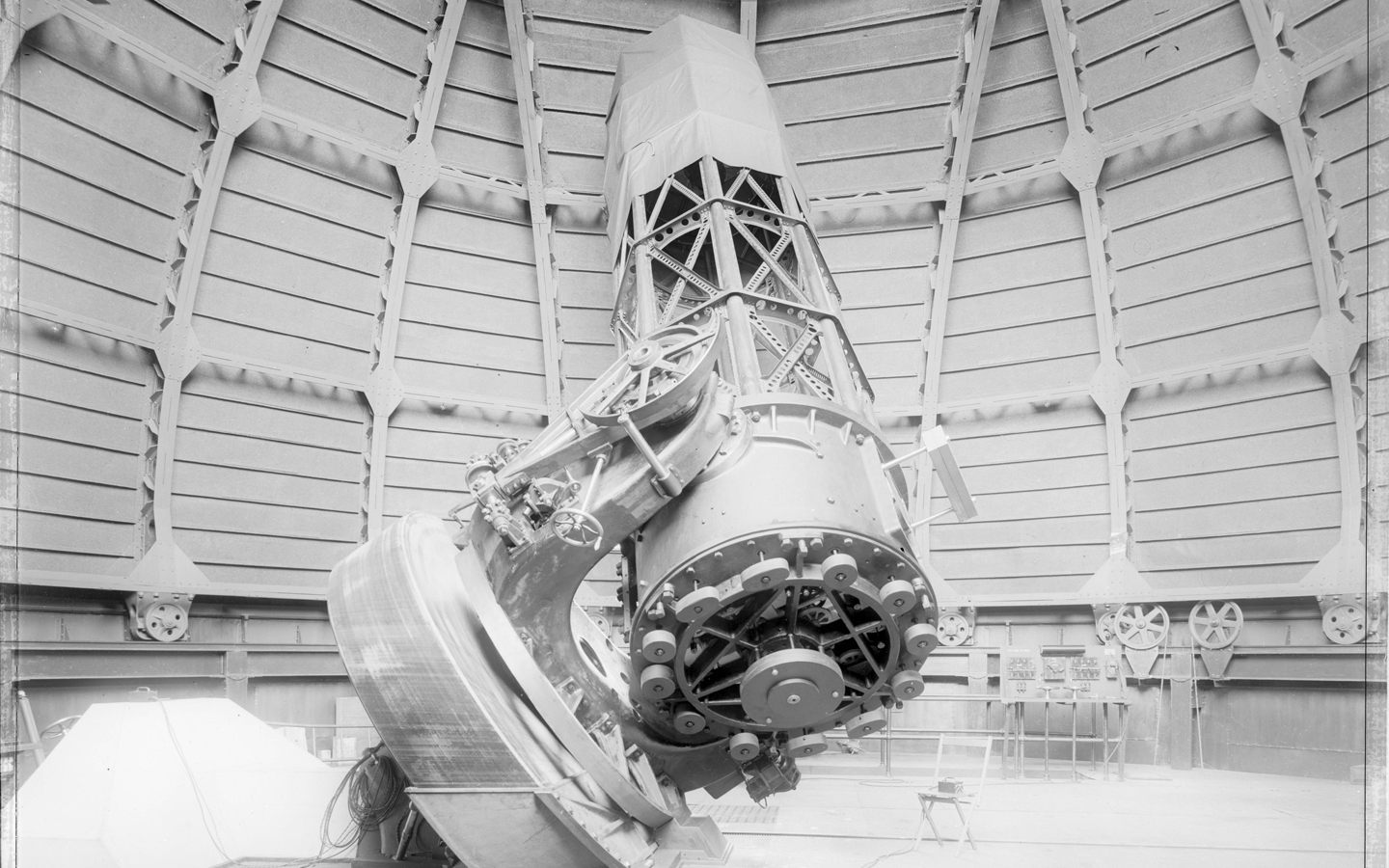

Completed in 1961, the Scottish Rite Masonic Temple at 4357 Wilshire Boulevard was designed by Millard Sheets and his team at Millard Sheets Studio. Sheets left his mark on Los Angeles, and while most Angelenos may not know him by name, they will certainly know him by his work. The quarter-century collaboration between artist Millard Sheets and financier Howard Ahmanson spawned a Sheets-designed Home Savings and Loan branch in several Los Angeles neighborhoods, many of which are fondly remembered as unique and beautiful. At the beginning of their partnership, Ahmanson told Sheets “I want buildings that will be exciting seventy-five years from now,” and these buildings are well on their way to fulfilling Ahmanson’s request. While Home Savings never left the twentieth century, its physical remains throughout the city are exemplars of Mid-Century Modern architecture, and the Scottish Rite Temple is no different. When asked why they chose to bank at Home Savings, many customers would cite the ornate buildings and reply, “we like to be associated with something beautiful.” When viewing the Masonic Temple, it is easy to understand why one would want to align themselves with the ideals of the organization.

The principal design consideration for Sheets’ buildings was artwork—a lot of artwork. There would typically be space outside of the building for a sculpture, and if not, the sculpture would often be attached to the façade. In the case of the Scottish Rite Temple, sculptors Albert Stewart and John Edward Svenson created eight monumental scenes with figures from Masonic history along with four massive, double-headed eagle seals over stained glass circular windows. Murals were employed by Sheets in most of his buildings, with the Temple’s created by Sheets and Sue Lautmann Hertel. The only remaining mural in the Temple—which depicts a crescent moon rising over an abstracted forest—resides in the museum gift shop. Gilding was another signature Sheets design aspect, and above the southern entrance are historical texts important to Masons, emblazoned in gold for all to see and be inspired by. Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, Devotion. Under each golden word, respectively, is a passage from the Gettysburg Address, the Declaration of Independence, Psalm 133, and a Mason text appealing to the “hearts of men of goodwill.” Sheets approached building design as he would a canvas—as an arena in which art was made.

The most essential Sheets design mainstay was his heavy use of mosaic, which you may have seen on his Home Savings commissions. Sheets Studio mosaics depicted scenes of local history or life, and these scenes tied the building to its location and to the people who used it and created a spatial context for all who entered. The art made the buildings special to that neighborhood, and they became portraits of the community. I have early memories of seeing the 16.5-by-40-foot mosaic depicting families frolicking by the seashore—Pleasures Along the Beach—that graced the façade of my local Home Savings in Santa Monica on Wilshire Blvd. The scene takes on a simulacral quality as it triggers memories of sun-drenched afternoons on the beach only a few miles west of the building itself. Its site-specificity and depiction of a local, beloved pastime transform it into a representation of local identity. Only a few weeks prior to the time of this writing, Pleasures was removed and taken to the Hilbert Museum of California Art at Chapman University in Orange County.

The Scottish Rite Temple’s mosaics operate in the same site-specific fashion. On the east end of the building, a colossal, four-story visual history of Masonry is enshrined in mosaic. This encyclopedic representation traces Masonic history from its foundational figures to its leader in California at the time, illustrating “King Solomon; the Persian emperor Zerubabel; the Crusader fort in Acre; the Rheims cathedral; Giuseppe Garibaldi in Rome; King Edward VII in London; American revolutionaries at the Boston Tea Party; and the first Grand Master of California, at his investiture in Sacramento.” Sheets not only wanted to tie the building to the history of its users but to associate California with a centuries-long history that can be understood by anyone viewing the mosaic. The very medium of mosaic lends itself to a historical, site-specific precedent in history recording, and its employ by Sheets is a very clever homage to the masters of the medium, the Byzantines. A perfect example of this is in the Sunu Mosaic (also known as the Vestibule Mosaic) in Hagia Sophia, which depicts Roman Emperors Justinian I and Constantine I offering their respective creations, the Hagia Sophia and the city of Constantinople, to Mary and Christ. The viewer is inside the very church, which is in the very city offered by their creators to Christ, and this religious devotion was the most important aspect of spiritual life at that time and place. A site-specific, spatial narrative is created between the viewer, the building, the city, and Masonic culture, and in turn, an identity is formed and confirmed. In Los Angeles, anyone viewing Sheets’ mosaic will know who has been a pivotal figure in Masonic history and will see Masonry traced all the way to California at the very place they are standing. The imagery instills a sense of historical continuity in the viewer, in the building’s patrons, and in the neighborhood. White walls cannot do that.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

The Marciano Art Foundation has left the travertine and art-clad exterior of the Masonic Temple intact, but as mentioned before, the very physical and metaphorical heart of the building has been stripped away. Sheets’ buildings were just as ornate on the inside as the outside, and the Scottish Rite Temple had many more examples of his artistry and design, which, I firmly believe, could have remained inside the gallery spaces in order to create a wholly unique museum space for Los Angeles—a space that does not ignore or whitewash local history or art, but truly generates a synergy between past and present.

The lobby is where most of the original marble walls are still standing. From them, the mosaic drinking fountains jut out from white drywall, surprisingly remaining visible but no longer in operation. These marble walls originally spread throughout the main auditorium spaces, above which more mosaics of Masonic figures were installed. All of these appointments have been torn out to transform these rooms into the blank galleries they are today. If retained, the original wall cladding and even the mosaics would interact with the art on display in the gallery. This interaction would allow connections between the art and the history of the building—and in turn, Los Angeles—to form. Viewers would be placed into a spatial narrative that encompasses the Marciano Art Foundation, contemporary art, Sheets’ designs, Masonic lineage, and Los Angeles history and identity. A true blending of all of these aspects would indeed lend itself to an idiosyncratic museum space that would tell each visitor exactly where they are and what this space means; it would be a space unlike any other. Unfortunately, the reality today is that when you are viewing art in the Marciano’s museum, you could be inside any of the seemingly endless supply of cookie-cutter galleries in the world.

Perhaps the greatest error is the lack of direct interaction between the gender roles of Masonry and contemporary art. The Freemasons are a men’s only organization, and art is the perfect rebuttal to any such coded gender norms. As a critique of gender exclusivity, the Marciano Art Foundation displayed the large-scale performance piece Obsidian Ladder by Donna Huanca. This was an excellent way to invite a female artist to command an auditorium built for exclusively male performances (a crucial part of Scottish Rite tradition involves performing in moralizing one-act plays). However, this attempt falls on its face when every indication of the building’s original use has been removed. Huanca’s work could have contrasted brilliantly with Masonic history. Every viewer could have seen a poignant juxtaposition of a non-male artist’s agency and the legacy of a men’s only organization. Sheets himself understood this, as every mosaic, though designed by Sheets, was assembled by Martha Menke. A woman assembled the history of Masonry that exists within and without the walls of an exclusively male space. Sheets undermined the expectation of gender norms under the noses of the Masons themselves, whereas the Marciano Art Foundation’s lazy attempt plays as half-hearted.

There is only a single mosaic remaining inside one of the main gallery spaces—a massive nature scene inlaid on a monolithic black granite background on the east end wall of the upstairs gallery. wHY covered it, placing a white drywall divider, just as large, only a few feet away from the original piece—effectively removing the mosaic from view and from conversation. The gallery flow does not invite viewers around the divider, and even when discovered by an intrepid visitor, the mosaic cannot be properly seen; the divider is too close, forcing the viewer to crane their necks upward in any attempt to view it. On the white wall, covering any semblance of uniqueness to the gallery space, was, on my visit, pithy Pop Art that attempts to comment on modern consumerism. With phrases like “I shop therefore I am” and “who owns what?”, Barbara Kruger’s artwork, poignant at the time of its inception, now comes off as a specious critique that perpetuates what it claims to rail against—and a clear harbinger of what Los Angeles’ legacy will be as more of our history is covered up by sameness and banality.

Yantrasast claims, “today we have more and more art, but fewer unique places to see it and or make it. Now, the often-cited accusation that Los Angeles is ambivalent about embracing its history has found the best site to link the past and present.” Yantrasast’s statement is indicative of a historical mindset held by developers in Los Angeles throughout the twentieth century, as boosters and speculators attempting to cash in on the dream that is Southern California transformed Los Angeles in order to package and sell it to the rest of the world. This paradigm required the razing of the old to make way for the new. The audacity of Yantrasast, to assume that Los Angeles is ambivalent about its history, is a slap in the face to groups such as the Los Angeles Conservancy, who strive to keep our history intact as representations of our identity. If any group is, indeed, ambivalent about LA’s history, it is the developers and designers like Yantrasast, who embrace our history with a wrecking ball and replace it with vapid facsimiles of luxury and versatility. Meanwhile, this reality translates into Los Angeles becoming continuously more expensive to live in, estranging its own residents both financially and culturally. The fact that Yantrasast’s white cube design and the Marciano’s contemporary art collection is already better represented in Los Angeles by MoCA, LACMA, the Broad, and even the Hammer, drips with irony. Yantrasast’s claim to uniqueness is only upheld by what remains of Sheets’ exterior, and in every way, Yantrasast proves himself to be the very blight he claims to cure.