Googie Architecture

SIGNS FOR THE FUTURE

TEXT CASEY PARSONS

VISUAL ASHLEY GUO

Nostalgia is best described as a sense of longing for a memory that is difficult to pin down, perhaps a desire for a past that never actually existed. As I drove down Hawthorne Boulevard, the floating bubble letters for Chips that emerged from the strip mall sprawl evoked this familiar feeling. Chips Diner looks like it came straight out of a television cartoon in the 1960s; the Jetsonian, retro-style interior with off-white leather and teal accents are inexplicably comforting, somehow reiterating the charm of the sun-baked, wide Southern California boulevards with low buildings and a sleepy pace. Like Chips, the Union 76 gas station on North Crescent Drive in Beverly Hills is another infamous “Googie” landmark, part of the architectural style that swept America in the 1950s, fueled by the Space Race and widespread automobile use.

As I pulled into the Chips parking lot and drove beneath the swooping awning of the Union 76, it occurred to me that these remaining Googies are more than relics of a style long passed. They were born out of a period of general optimism for democracy, experimentation, and a growing love for technology. Undeniably, the most disruptive technological advancement at the time was the car. Cars imposed a new scale, rhythm, and symbols onto the urban landscape, and Googie was the first architectural reaction to embrace the horizontality of the automobile era. It is no wonder that the style became popular as a consistent aesthetic for drive-ins, gas stations, coffee shops, burger joints, diners, and motels—all of which were developed to keep up with the quickened rhythm of daily American life.

Googie introduced a roadside vernacular architecture that captured the imagination of the American middle class, spurred by the momentum coming out of the deprivation years of the Great Depression and wartime rationing of goods. Not only were cars shaping urban development, but in the post-World War II era, burgeoning, the newly prosperous population was intoxicated by the power to purchase. The bright colors and flashy style of Googie architecture not only expressed the climate of technological optimism but emboldened architects and designers to create an infrastructure that would enhance development.

Googie architecture marks a pinnacle turning point in the nature of American urban design. This style represents a technological transition that became the new American dream. As electricity, radios, refrigerators, and the car became commonplace consumer products in the American home, Googie as a popular style ensured and democratized the increasing commercial capitalism of the American middle class. These buildings fostered economic gain, enabling new modes of marketing strategies to increase consumption and contribute to the swelling post-war economy—just like cars became a part of the family, lifting burdens and bestowing mobility.

Googies built a vision of a future that was neon orange and bright green. The entire family would be included; the innovations of science allowed drive-ins and diners to stay brightly lit twenty-four hours a day; motels would bring Americans further out of their comfort zones without fear. Perhaps this is overstating the effects of raunchy diners and retro gas stations, but undoubtedly there was a notion that economic progress would not slow down so long as the car kept driving faster.

Chips in Hawthorne still captivates passersby from some distance. The sign is kinetic and grabs your attention with its floating, asymmetrical blare. On its left are three staggered pylons linked by the floating letters; to the right are drums of metal mesh that are no less visually striking. Less was not more; Googie style was about pluralism. As I approached the seemingly unremarkable box-like building, I could feel this hopefulness, and while it resembled the stripscapes with shingled roofs and undervalued textures, it was different from the bland visual clutter Angelenos are accustomed to. The colorful, quirky design struck me as oriented toward some future that included the will of the average American like me. It would safeguard the commoner, provide spaces made for play—places made to last.

Googies ushered in an era of advancements that would transcend technology and foster social and economic prosperity. In his 1985 book, Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture, architectural historian Alan Hess pronounced that the “24 hour drive-ins cut democratically across class lines by offering the common denominator of citizenship in the age of speed.” Of course, the idea of a booming economy is that everyone will prosper. While Googies became popular on the cusp of the Civil Rights movement, marketed as accessible spaces with a unanimous consumer experience, they were also part of the racist and classist landscape of the 1960s. Architecture is only as good as the practices it facilitates, and as racial and socioeconomic disparities continued, the car and the drive-in perhaps emboldened the willful ignorance of increasingly polarized cities. Googies marked a new phase in the urban experience, and as spaces open to anyone with money to spend, they superficially demonstrated that we were in a new, more evolved age. Googies were designed to encourage increased spending, increased movement, and champion the notion that the good days had come—and at least on the surface, everyone was welcome. However, the suburban sprawl which eagerly integrated Googies also prompted the first step in the white flight that has perpetuated stark racial and class divides in this country. Douglas Haskell, editor of House and Home, saw Googies as a style of excess. Despite his discomfort, Haskell noted that the flamboyance achieved more than just catching the eye. While Googies did not solve any of the social issues in the fifties and sixties, they did embrace technology and showed it as synonymous with the good life. They emboldened free exploration unhindered by accepted taste. Googies were announcing a new age without asking permission.

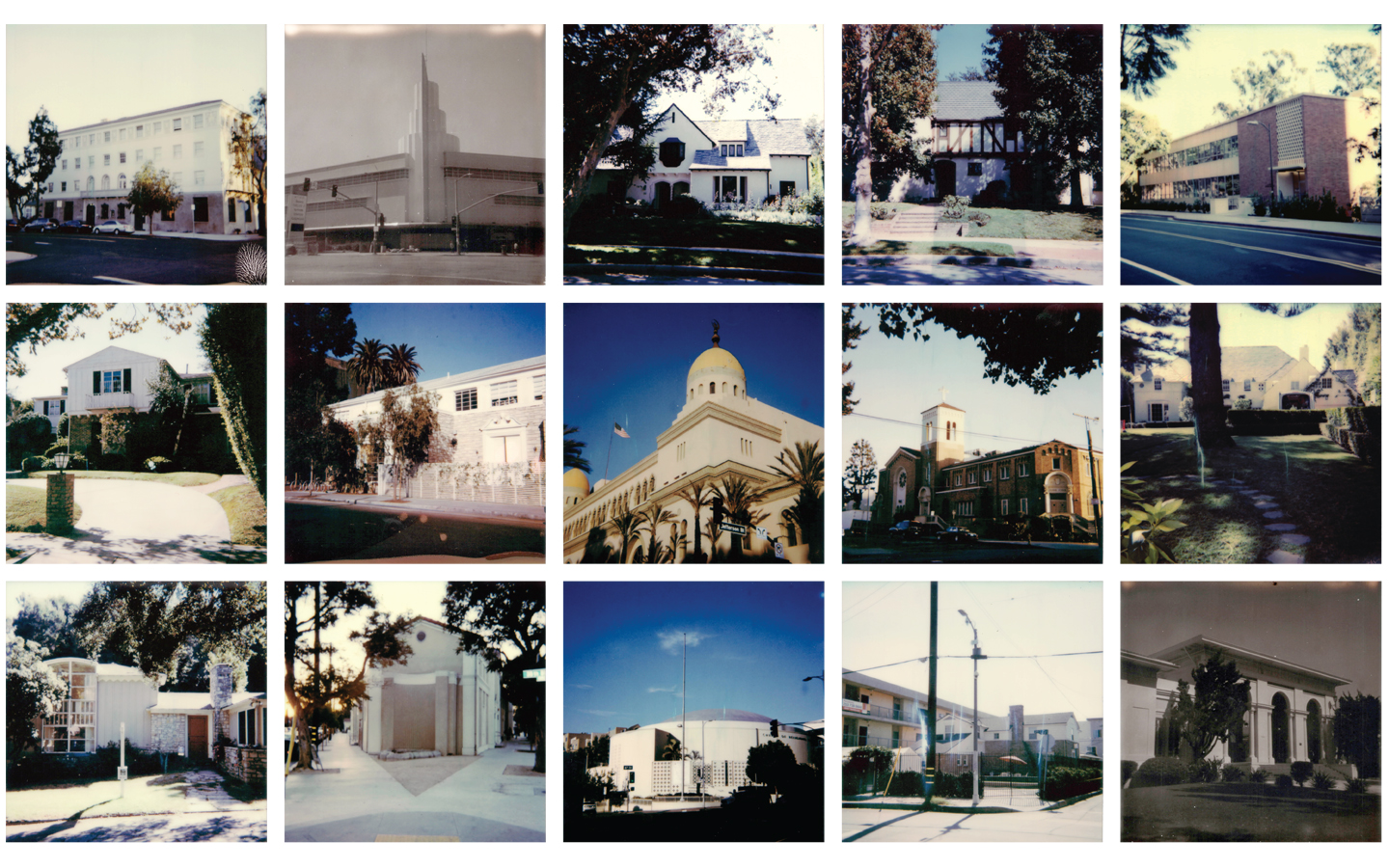

Today, Googies stand as reminders of futurist architecture that influenced cultural practices of the time. The structures were meant to look abstract; even now, the style appears to ignore gravity altogether. Futurist architecture was, for the first time, integrated into residential neighborhoods. This, of course, changes the dimensions of the future being announced. It was a future that would be paid for by commerce and guided by the consent of the consumer.

The Googie style is not like other architectural fads. It does not fit easily into an aesthetic category that leads into the next design phase and has often been conceptualized as a part of a media blink of the past—and yet it infiltrated American consumerism on a deep level, introducing and facilitating the reliance on the car as a pinnacle asset of American economic growth. Googies stand for a cultural moment that jettisoned consumerism and popularized a visual culture that could be easily recognized, making one feel at home even if far from it. The buildings from this era do not hold up because consumer culture is increasingly de-materialized as the growing gig economy replaces traditional jobs and commerce shifts from physical locations to the digital sphere. Consumer convenience today stands as a multi-billion dollar industry that spans from Amazon to McDonald’s, delivering commodified, quick experiences that are less personable—if not entirely separate from the relationship to one’s community. I don’t think that Googies created this, but they certainly stood as precursors for the landscape of quick transactions to come. There is something refreshing in knowing that it all used to happen in plain sight; we used to know exactly how much energy it took to drive and buy a hamburger and fries. Human interaction used to be more spontaneous, and time operated with different constraints, allowing space for casual run-ins with neighbors at family-owned establishments. It seems that the market that Googies relied on no longer fits our consumer habits. We rarely pass an establishment and decide to go in; instead, we depend on internet reviews to direct us to a desired product or experience. As a culture, it seems we aren’t as excited by new things are we are by someone telling us “you will definitely enjoy this.” Part of this stems from the fact that in the gig economy, time as a resource holds far more weight than in the era of nine-to-fives and pension plans—which means that we spend our time like we spend our money. Now that we have more options to choose from, it seems as though individual autonomy is greater than ever before. However, others are telling us what to do in more diffuse and anonymous ways. From Yelp to ad targeting and product placements on the internet, it is taking more and more to generate our own opinions. In a landscape of corporate power, many experience a sort of paralysis to challenge the powers that be. While we may be more efficient today, this efficiency-driven mindset is limiting; it removes the possibility for new and more expansive experiences. In our haste for productivity, our understanding of the political, cultural, and environmental ramifications of our day-to-day activities are often forced to take a backseat.

The next phase of this future is already materializing. The Union 76 Station at 427 North Crescent Drive was designed for the Los Angeles Airport. It was meant to complement the theme of the other buildings with its circular, flying saucer-shaped overhead, supported by four tapered legs. The sweeping canopy is striking, but the people at the pumps beside me didn’t seem to notice. They were merely filling their tanks with gas—one of the few chores that has yet to be answered by new technology. The mindset of instant gratification has led us to overlook details of daily life that used to be sources of enjoyment. We go to complete this task and get out as quickly as possible; it is an annoyance to run errands like this because it isn’t necessarily a “chosen” use of our time, like going out to restaurants or museums. That is, pumping gas is not an enjoyable experience—and while perhaps a necessary task, it is also a reminder of polluting practices that are commonplace in our culture. Many people are aware of social and environmental issues but do not have the time nor the resources to do anything about it. In our twenty-four-hour news-cycle and media saturated environment, it is difficult to find a foothold in something as large as climate change, an issue that is omnipresent and yet remains nebulous in terms of actionable responses. As a result, willful ignorance or passive discomfort about such growing issues is the norm. It feels almost satirical to be gawking at the design of this Union 76 when its function, once considered high-tech, is now an indicator of our planet’s destruction. And yet, even the gas stations that remind us of the dependence on polluting oil industries are merely signaling an issue too big to be solved right this second, and complacency follows. I wonder if there will be any visual roadside vernacular compelling enough to turn heads, to get people to meander off of routine desire lines and commutes—perhaps even to spur them to question their own accepted practices.

Building for a changing world poses uncertainty about the future. New design in cities must incorporate technological innovations while remaining skeptical of the ones that got us here. Googies are a reminder of a different time, marked by the advent of technological progress and the drive for consumerism to thrive as a cultural pillar. Perhaps they stand as reminders of spaces for spontaneity and play that were built into the urban experience. Googies remind us that the built environment does inform social trends. With their closures and a rapidly changing landscape in terms of technological infrastructures, it is difficult to predict what kind of roadside service will take their place. The only certainty is that the future ahead holds new challenges.