Paul R. Williams

TEXT VANESSA DE HORSEY

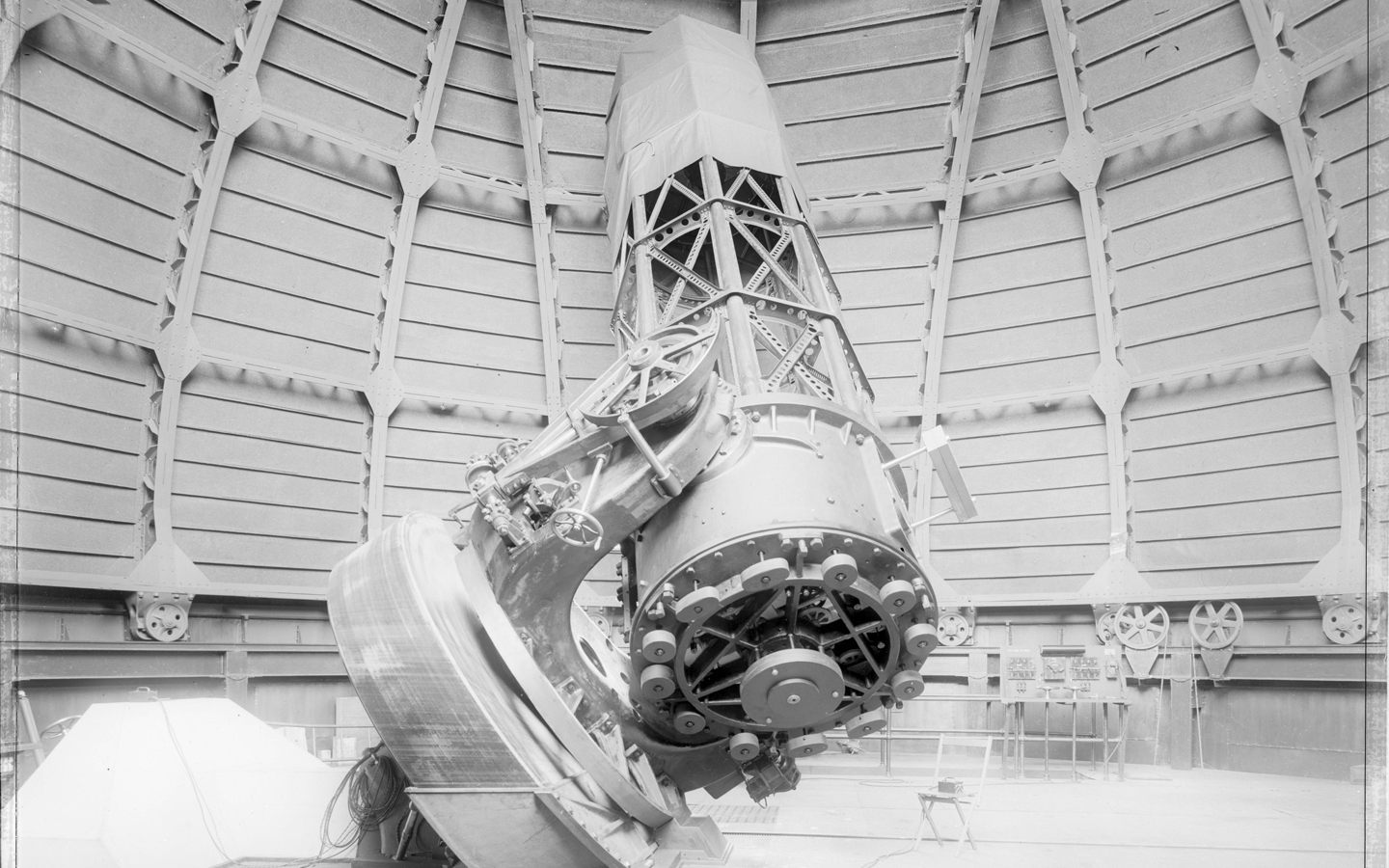

VISUAL FARIDA AMAR

99 years after he opened his architectural firm, the legacy of Paul R. Williams remains interspersed throughout Los Angeles, invisible in plain sight.

While in Miami to visit our grandmother, my brother and I discussed some projects he was working on in his landscape architecture studios. I mentioned that one of his ideas reminded me of a particular Paul Williams project (what it was I couldn’t tell you; the sheer magnitude of his work is hard to keep track of). My brother hadn’t heard of the architect before. Thinking it might interest him, I handed my brother the book I’d brought with me: The Will and the Way, written by Williams’ granddaughter, Karen E. Hudson. A few minutes later, while I was in the other room, my brother shouted to me: “Is this really true?” I didn’t quite know what he meant, so I replied with a hesitant “…Yes?”

I returned to the living room and found my brother looking somewhat vexed.

REED: You mean to tell me that Paul Williams designed and built thousands of buildings?

VANESSA: Yes.

Reed furrowed his brow.

REED: In the 1920s?

VANESSA: Yes. Well, that’s when he really got his start.

REED: And he was black?

VANESSA: Yes.

REED: In the TWENTIES, he did this?

My brother began pacing around the room, flipping through the pages. “How have I not heard of him before????” He started fuming—it seemed unconscionable that his architecture studies hadn’t taught him about this illustrious trailblazer. My brother’s reaction gave me pause: how few people really know about Paul R. Williams?

AN UNLIKELY PIONEER

Paul Revere Williams was born in 1894, thirty years after the abolition of slavery. He was orphaned before his fourth birthday and subsequently adopted by friends of his parents, a loving couple who encouraged his artistic efforts from the time he was a small child. While in elementary school, Paul’s love for drawing led to his reputation as the class artist; outside of school, he began developing his work ethic by selling newspapers on street corners to help support his family. By the time he was in high school, Paul had decided to become an architect.

In 1908, the Ford Model T debuted; in 1912, the moving picture industry began to crop up in Los Angeles. As counselors and peers cautioned against entering an industry dominated by white professionals and white wealth, Paul’s adoptive parents continued to encourage him, and his own passion grew too strong to ignore. On his decision to become an architect, Paul explained: “This was the turning point in my life because I realized I would forever question my right to be all that I could be if I allowed others to discourage me because of the color of my skin. I developed a fierce desire to prove to myself that I could become one of the best architects ever. I knew I had the will. All I had to do was find the way.” He pushed forward with almost unnerving tenacity. In 1914, at twenty years old, his design for a neighborhood civic center in Pasadena won first prize in a competition; he then won first honorable mention in architecture at the Chicago Emancipation Celebration and placed third for the Perling Prize, an All-American competition in New York. Paul’s talent was already unmistakable, but it was far from enough to compete in the white-dominated industry. “I realized that the only chance I had of being accepted in the elite world of architecture was to compete on individual merit,” Paul wrote.

His next step was to increase and sharpen his expertise in every way possible. Paul enrolled in Los Angeles Art School, then the Beaux-Arts Institute in LA, where he won the Beaux-Arts Medal for excellence in design. He took courses in color theory, rendering, and interior design, and started working at an architectural firm. Being in the workforce provided valuable insight. “I decided that I would do things faster, more efficiently, and better than others in order to be judged for my abilities rather than simply dismissed because of the color of my face.” He enrolled in an engineering program at USC, which included business and math courses. His time at USC equipped him with both the logistical education to succeed in the workforce and the precision that his architectural work eventually became known for. In 1917, he married his wife, Della. Two years later, he became the first black graduate of USC. He then worked with John C. Austin, helping the firm design and build thirty schools, the Shrine Auditorium, the Chamber of Commerce, and the First Methodist Church of Los Angeles. He was appointed to the first Los Angeles City Planning Commission. In 1921, he was a licensed architect in the state of California; the following year, he opened his own firm in the Stock Exchange Building. In 1923, Paul Revere Williams became the first black member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

His prodigious talent was both innate and undeniable, but what separates Paul Williams from most others was his unending drive to improve himself. He went back to school numerous times to study areas that would augment his abilities. He tended carefully to the desires of his clients. He never remained fixed in a particular style; he pushed, evolved, looked for challenges—and accepted each hurdle with a vigorous grace. In many ways, Paul was a revolutionary who wound the clock of progress.

TURNING POINTS

The true start of Williams’ career began when Louis Cass, a friend from high school, commissioned a new house in Flintridge—a new development started by Senator Frank Flint (the area is now the city known as La Cañada Flintridge). Senator Flint, whom Williams sold newspapers to as a young boy, then asked him to design numerous other homes in Flintridge. This became the catalyst, both professionally and financially, for Williams to open his own firm.

Winning a commission in 1931 for the residence of eccentric auto manufacturer E.L. Cord resulted in a new era of business. After their initial meeting, Williams spent twenty-two straight hours designing the original plans in order to present them the next day—an astonishing turnaround that would set him apart from his competitors. (The other architects Cord consulted with provided a two to three-week timeline for preliminary plans.) The estate Williams designed in Beverly Hills was over 30,000 square feet, and because the Cords frequently hosted parties among the Los Angeles elite, the house became known as “the ‘showplace’ of Beverly Hills.” Along with the endless list of residential commissions that resulted from this opportunity, Cord also acted as the liaison between Williams and Adam Gimbel, who later asked Williams to design Saks Fifth Avenue in Beverly Hills.

By the time he retired in 1973, Paul R. Williams had amassed an incredible dossier of accomplishments. He designed and built over 3,000 buildings, around 2,000 of which were homes. That comes out to about fifty projects per year, from concept to completion—or four per month, or one per week. He had additional offices in Washington, DC and Bogotá, was a licensed architect in California, Washington DC, New York, Tennessee, and Nevada; received an AIA Award of Merit; was the first black inductee to the AIA College of Fellows; won the NAACP Spingarn Medal; and was internationally known as an architect to the stars. In addition, he served as a champion of his own community, both as an architect and as a prominent figure; he was appointed to the National Monuments Committee by President Coolidge, to the California Housing Commission by Governor Earl Warren, and to the National Housing Commission by President Eisenhower. He designed the Angelus Funeral Home and the 28th Street YMCA; the Beverly Hills Hotel; the Music Corporation of America Building; the film-famous Ambassador Hotel; Langston Terrace, the first federally-funded housing project in the United States; homes for Lucille Ball and Frank Sinatra; and was on the team that designed the Los Angeles International Airport.

SOCIAL UNDERTONES

“I had a feeling that The Polo Lounge and the Fountain Coffee Shop would

become landmarks. Yet once again I found myself designing places that

would not welcome me had I not been Paul Williams, architect.

Some things change, some things remain the same.”

Paul Williams designed homes for many of the wealthiest, most elite members of the United States, from movie stars to politicians to captains of industry. He created upper echelon landmarks like Saks Fifth Avenue in Beverly Hills, the Ambassador, and the Beverly Hills Hotel. He is, in many ways, responsible for transforming Los Angeles into the pinnacle of glamour that it’s known to be—designing a copious number of homes in neighborhoods like Hancock Park, Beverly Hills, the Pacific Palisades, and the Hollywood Hills. All the while, Williams remained, both legally and socially, confined by his race. Despite his accomplishments, celebrity, and accumulated wealth, Williams remained in his small home “in a restricted area of Los Angeles where Negroes were allowed to live.” He rode in the “Jim Crow” car on trains when he had projects on the East Coast. He was restricted in his choice of restaurants. He was accepted, even adored by, many of the most powerful white figures in society. But he was still an African American.

As the SurveyLA: The Los Angeles Historic Resources Survey explained in its report, African American History of Los Angeles, “The period of significance begins in 1915 with the widespread use of restrictive housing policies and racial segregation in Los Angeles,” which prohibited those who were not white from living in designated areas—often, no surprise, the more desirable neighborhoods.

In 1924, the National Association of Real Estate Boards established a “code of ethics” which prohibited realtors from introducing “members of any race or nationality” to a neighborhood that would threaten property values. If a real estate agent violated this code, they would lose their license. As a result, many realtors practiced “steering”—they would not show properties in white neighborhoods to “unwanted groups.” Invariably, blacks would be steered away from white neighborhoods. This code stayed in effect until the late 1950s.

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer that for courts to enforce these covenants was unconstitutional; however, while their use decreased to an extent, other tactics remained in place to prevent racial integration in many neighborhoods. Restrictive practices came from homeowners associations, the Los Angeles Real Estate Board (which would not allow black members), banks (redlining), developers, and individuals alike. Intimidation practices were widespread as well, particularly when new laws allowed other races to move into previously white-only areas. The Urban League counted 26 forms of said practices in the 1950s, which “ranged from polite requests to leave, to bombs, vandalism, and death threats. Such incidents rose in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly after the courts struck down restrictive covenants.” These discriminatory practices applied to the famous and successful, too. “In 1948, world-renowned actor, pianist, and singer, Nat “King” Cole, bought an $85,000 home in the very desirable and upscale neighborhood of Hancock Park,” and was subjected to intimidation, an affidavit that referred to the neighborhood’s covenant, and incurred both harassment and vandalism. The realtor who sold the house was also threatened with the loss of her real estate license and “a serious automobile accident within a few days” for her role. It was not until the Fair Housing Act of 1968, following the civil rights movement, that discrimination in housing practices became illegal. By the time the law was enforced in 1970, Paul Williams had been an architect for 50 years.

His success in white society had to do, in part, with his understanding and acceptance of the current state of the world. He never tried to live in one of the prestigious neighborhoods that he helped evolve; he did not sit at the front of the bus; he did not “demand” anything, in fact. His entire strategy was carefully curated to establish himself as a non-threat—and in that way, he won the trust, and many times the friendship, of his white clientele. In the introduction to Karen E. Hudson’s book, Paul R. Williams, Architect: A Legacy of Style, David Gebhard states, “His white clientele certainly engaged him because they admired his architecture, but one suspects that many of these clients also came to him because he was a talented black professional … A segment of the white [upper-middle class and wealthy] could demonstrate their feelings about the equality of the races by engaging him.” The way he worked for his own community was almost as subtle. He took on projects that he cared about and made changes from his position of power, but always without force. He never stepped on anyone’s toes. He remained polished, poised, and polite.

A COMBINATION OF DETERMINATION, PERFECTIONISM, AND PASSION

“Building styles change with time and fashion, but I measure my worth as an architect by my ability to please my client,” Williams explained. He was precious about his work, not his ego. “Williams’ designs were much like the man himself: affable, well-mannered, gracious, and graceful,” architect Max Bond attested in Harvard Design Magazine (1997). “Like the movies, his work helped define a California style of self-assured, easy worldliness.”

His life’s work was rooted in an understanding of architecture’s purpose and power: a desire to create spaces that would please, delight, and function seamlessly; his ability to read his clients and bring their ideas to life; his willingness to evolve; his tendency to put work first and leave ego behind; his faith in the impact of his practice. The night before his retirement dinner in the spring of 1973, he wrote, “While I’ll always treasure my work on such buildings as the Los Angeles County Courthouse, the Hall of Administration, the Federal Customs Building, and, of course, the airport, my favorites will always be the homes.”

Like their architect, Williams’ homes were not loud or ostentatious. His designs existed with an effortlessness that made them ideal habitats. Such a tour de force is only achieved through extreme dedication: attention to detail, deep understanding of the project’s variables, deliberate touches. Each curve and line, the area of each room, the placement of spaces relative to each other. His motto became, “Good design is the pleasing assemblage of parts, not the assemblage of pleasing parts.” Williams’ work was a perfect and delicate balance of function and art, practicality and pleasantry. These invisible signatures flow through his buildings, and throughout the city.

Paul Williams understood the blueprints of society as well as he understood the architectural plans in front of him. He designed himself, his practice, and his own work in response to these social conditions. In discerning the obstacles and challenges in front of him, he had an astute ability to master them, finding or creating a solution in response. He dressed impeccably, providing a subconscious precursor to his elegant work. He completed projects with exponential speed compared to his contemporaries, a skill he refined to give him an edge. He developed marketing “tricks,” as he called them, to land clients that would otherwise turn on their heel when they discovered he was not white like them. One such trick was to ask the now-hesitant prospective for their budget and follow with a sympathetic apology, for he, unfortunately, couldn’t take on projects for a rate so low—but as a courtesy, would happily provide them a free consultation to help them work out some of their ideas. Then, “I sat across the table from them and asked questions about their new home … As they shared their ideas, I sketched upside down so their ideas would come alive—right side up—before their eyes.” Paul leveraged his profound social savvy to put the client at ease by establishing a physical barrier between them, then delighted and impressed them with his acuity and talent. And in gaining these insights about the client’s lifestyle, he would map out plans suited perfectly to their needs and desires. This erudite ability stretched far beyond attention to detail; Williams had an innate talent for making a home both beautiful and exquisitely functional.

“Some architects like designing just the exterior of buildings because that’s what everyone sees. I like designing both. After all, interiors are more important to the people inside the buildings. Part of my job as an architect is to create a pleasant environment for people to live and work in.”

From the interior flow and the placement of rooms to the landscape, the unique features, and the desired style, each client received far more than a building when they hired Paul Williams. He adored this process, which is likely why he had such a gift for it. As he admitted, “I was still a perfectionist and tended to every detail. It was never enough to simply design a building.” Many of the most impactful features would seem subtle to the ordinary viewer, but they made Williams the sought-after architect he was. For one client, who had a wife that struggled to drive in reverse, he had a turntable built in the driveway so she could leave the property without backing up. For John Zublin, who couldn’t swim, Williams designed a pool narrow enough for Zublin to paddle in a canoe with the oars safely touching the sides of the pool from any position. For the El Mirador Hotel in Palm Springs, Williams “wanted the hotel to recapture its original resort atmosphere,” so he hand-selected palm trees for the property and chose exactly where each was to be planted. For his own home, he designed the exterior and interior as well as the furniture—creating an idyllic residence for his wife and children.

As Williams’ fame and fortune grew, he found new avenues to impact his own community. “Although I was thrilled to have so many opportunities to design mansions, I was always concerned about affordable housing for those less fortunate.” On the 28th Street YMCA—the first to cater to the African American demographic—he stated, “I knew how badly we needed [a YMCA] in our community. I also knew how important it was for young people to have role models, so I incorporated likenesses of the abolitionist Frederick Douglass and educator Booker T. Washington into the ornate design of the facade of the building.”

Years later, Williams became a founder of the Broadway Federal Savings & Loan, along with his friend H. Claude Hudson—a dentist and civil rights activist. (Karen E. Hudson, who has served as the prominent source to chronicle Williams’ life, is the granddaughter of both men via the marriage of Williams’ daughter Marilyn and Hudson’s son, Elbert.) Paul was particularly passionate about this position—one of his first real opportunities to enact meaningful social change. As he emphasized, “For too long white-owned banks had kept Negroes and other minorities from getting home loans, a practice called redlining. I spent my entire adult life designing homes for others and believed that the survival of a community depending on their homeownership. I desperately wanted Negroes to be able to own their own homes.” In a little-known twist of fate, this role also led to the single most iconic architectural project in Los Angeles: Pierre Koenig’s Stahl House, or Case Study House No. 22, of 1960. Despite all

of the other banks in Los Angeles refusing to take on the project, Williams advocated for the effort, and Broadway Federal Savings & Loan supplied the loan for Koenig to build the cliffs-edge masterpiece of modernity. Broadway Federal, which Williams redesigned, was also the location Williams selected to store his archives. Given the combination of his history with the building, family relationship with the institution, and its location in Williams’ own community, there seems no better place to house the architect’s life work. The structure exemplified both his professional triumphs and his civic impact.

Though Williams worked quietly in his efforts to advance social progress, he measured his true success by his ability to give back to his own, simultaneously hoping to inspire future generations. Upon receiving the NAACP Spingarn Medal for excellence in his profession, Williams said, “I was very honored that the NAACP recognized me. The regular history books may never be interested in my accomplishments, but I know I will be recognized in Negro history journals if only for having won the Spingarn Medal.” Paul died in 1980 at the age of 85, renowned across community, racial, state, and international lines. Twelve years after his death, the riots that followed the Rodney King verdict devastated Williams’ home community of South Los Angeles. The reaction to the four LAPD officers’ acquittal after the senseless beating of King sparked outrage in the black population, renewing conversations around civil rights, racial injustice, and social tensions. The riots resulted in 63 deaths, 2,383 injured, over 12,000 arrests, and approximately $1 billion worth of damage. As thousands protested over six days, Broadway Federal Savings and Loan went up in flames, and the majority of Paul Williams’ records, drawings, and notes turned to ash.

A LEGACY SHROUDED

When I spoke with the Los Angeles Conservancy, I assumed that the world of architecture would be familiar with Paul Revere Williams. Is there anyone worth celebrating more than a person who, when faced with astronomical odds, managed not only to succeed but to build an entirely new world? There is perhaps no better example of the promised American Dream than Paul Williams. One would hope that accomplishments of this caliber would be lauded, celebrated, renowned across the board. In fact, precisely the opposite has followed. While renowned during his lifetime, most traces of his legacy have, surprisingly, faded into the past.

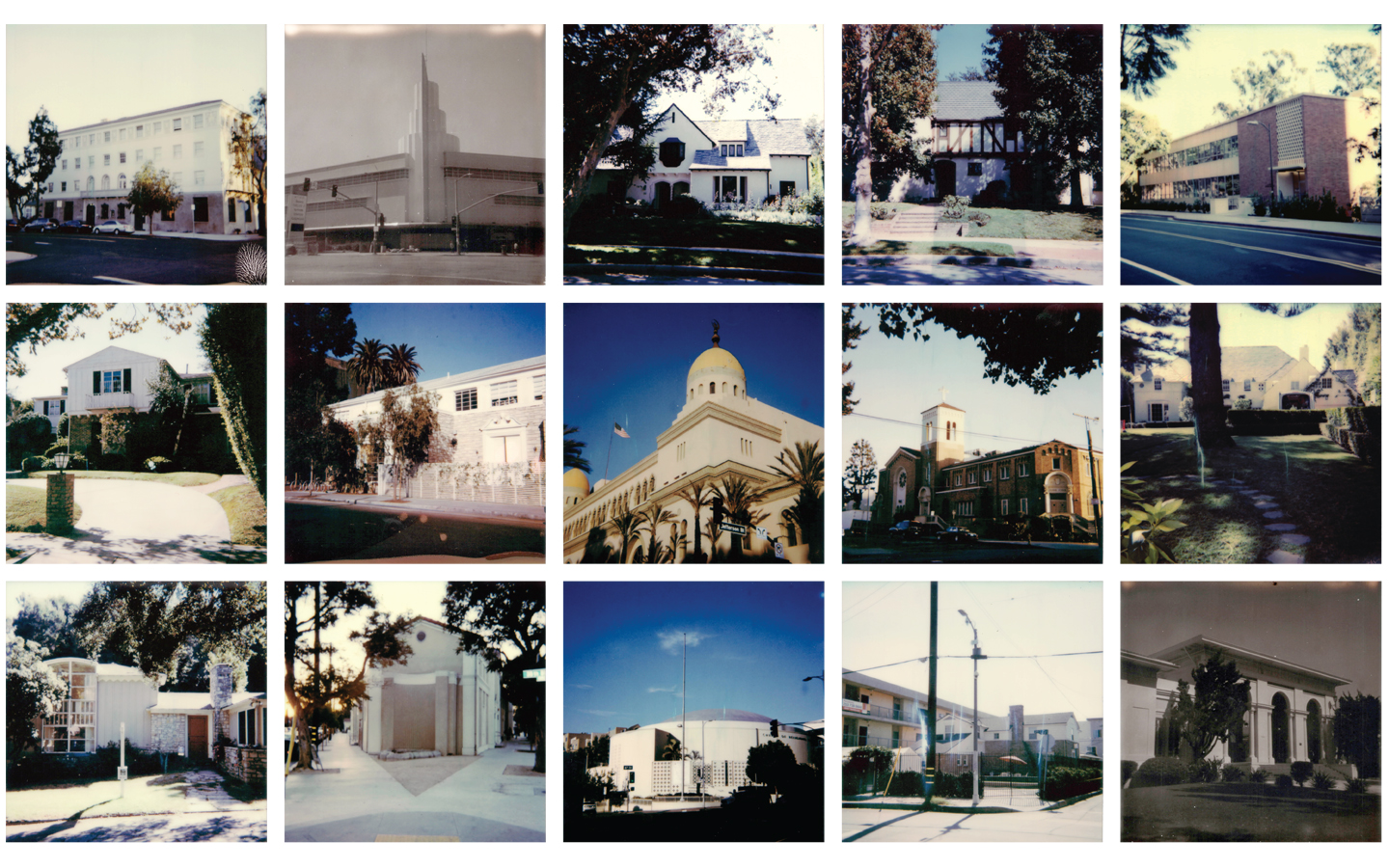

There are various reasons for Paul Williams’ shrouded legacy. First, the destruction of his records, coupled with the era he worked in, means there is far less information remaining about him than someone who worked later, or who still had archives to explore. He did not have a “trademark” style (save for his love of curves, which are found throughout the interiors of his designs). As such, a Paul Williams design is not immediately apparent—the exteriors do not scream his name the way many other esteemed architects’ works do. Instead, Williams shaped Los Angeles subtly, steadily—almost silently. Most of us who live in LA, or have even visited, have likely seen dozens of buildings (if not hundreds) that he designed and not known it. Hancock Park has, I would guess, at least 100; Beverly Hills has around 80; Pasadena, Bel Air, the Hollywood Hills, Brentwood, Los Feliz, Glendale, and La Cañada-Flintridge each have a dozen, if not far more. There are over 2,000 Paul Williams homes in Los Angeles, save for the 45 that have been demolished or destroyed by fires. While realtors advertise his name when one of his homes goes on the market, most people—even architects—will never know who he is.

In the weeks following my return from Miami, I spoke to my brother often; he was impassioned about Williams. He asked others in his architecture school to see if they had learned about him. The answer was a resounding, “No.” When he spoke to his architectural theory professor, who we thought would have some information on the omission of Williams from the curriculum, we discovered he “had heard the name,” but little more than that. The professor stated that their University doesn’t teach about Williams, and, more generally, “he isn’t touched upon much in education.” The frustration my brother felt was not only based on Williams’ achievements and historical significance. What seemed to make the least amount of sense from his perspective was that Williams’ work is a tangible representation of various values championed in architectural theory courses. Influence of built environments on cultural evolution. Architects and their designs’ social impact. How buildings and city planning affect communities. These ideas, while discussed as tenets for conscious design, tend not to have many concrete examples.

There is another, perhaps more glaring, variable in considering the deafening silence surrounding Paul Williams today: the combination of institutional and systemic racism. Shawhin Roudbari, Ph.D., a faculty member of the University of Colorado Boulder’s Program in Environmental Design (ENVD) who teaches about the ethics of design for social change, provided some insights during a phone call (graciously arranged by my brother). Roudbari clarified first that Williams was the prominent inspiration for a generation of architects in the 1960s, in the heat of the civil rights movement, particularly in the architecture program at Columbia University. This period in the late 60s stands as a clear peak in enrollment of black students in architecture. Then came the racist backlash of the 1970s; unfortunately, schools have still not recovered the high demographic that occurred fifty years ago.

This has a critical impact on the field today. “Generally, black architects are under-recognized and almost not studied at all,” Roudbari regretfully explained. “Because of the history of race and capitalism in the US, black folks and black architects, in particular, have been held at arm’s length from the loci of economic, symbolic, and professional power. Furthermore, the underrepresentation of black Americans in our profession and the lack of vision (and racism) of many educators means that people hardly recognize amazing designers like Williams when they do break through institutional racism and institutional barriers. And when black architects make it past such barriers, the next big challenge is being included in architecture’s ‘canon.’ Few, if any, black architects are acknowledged in most—almost all—histories of architecture.” There is, however, a faint silver lining: “While we lack a critical mass of black architects to elevate his legacy, frontrunners like Williams are still celebrated in the black community. And, there are various organizations, individuals, and educators that are working ‘decolonizing’ the canon to include the pioneering work of architects of color in our teaching, learning, design,” Roudbari attested.

DESIGNING THE FUTURE

“Good architecture should reduce human tension

by creating a restful environment and changing social patterns.”

In The Will and the Way, Williams elucidated that “The most important lesson I learned was restraint … a matter of choosing and carefully planning for the total effect.” He spoke about design elements in this case, but I believe he consciously embodied this ethos in every facet of his life. Paul Williams was nothing if not deliberate, and his superior perception became the driving force behind what was, in effect, his own Midas touch.

When infrastructure is explicitly designed against you, perhaps the most effective form of action is to build something else. At the outset of every obstacle, Williams resolved himself to find “the way”—to improve himself, to stand out, to make himself invaluable. He was proactive and solution-oriented, identifying areas that would help him succeed, then immediately resolving to get there. This is not to say that anyone could do what he did, but it reveals the fact that initial barriers may not be as impenetrable as they first appear. Paul Williams saw a world that did not want to accept him, so he did what he believed to be the obvious: he made himself too valuable, too talented, and too pleasant to ignore. In doing so, Williams undoubtedly changed the minds of society in its prejudices, exemplifying the hard-working American who came from nothing, odds stacked against him, and built his own personal success brick by brick.

Williams’ impact, then, worked as he did: non-threateningly and with the utmost care. Whether Williams helped to dismantle racial bias on an individual level or served as a sterling example for the white minority who believed in racial equality, his impact on social norms is difficult to quantify. We can assume, at least, that his influence steered things in the right direction, even if we can’t quite assess the magnitude or distance that he helped push things forward. While his legacy has been overshadowed—muted, lost, and forgotten over the years—the impact of his resolute and dynamic design process remains woven within the urban fabric of Los Angeles. As Williams said, “Creating the environment is an important background for the acceptance of change.” In more ways than we can count, Paul R. Williams was a revolutionary.

“Don’t let anyone keep you from achieving your dreams, Paul.

You can be whatever you want to be—as long as you have the will and the way.”

In a note to Williams’ first grandchild, Paul Claude Hudson, May 8, 1948