Lincoln Heights Jail

CRIMES FORGOTTEN

TEXT VERONICA AN

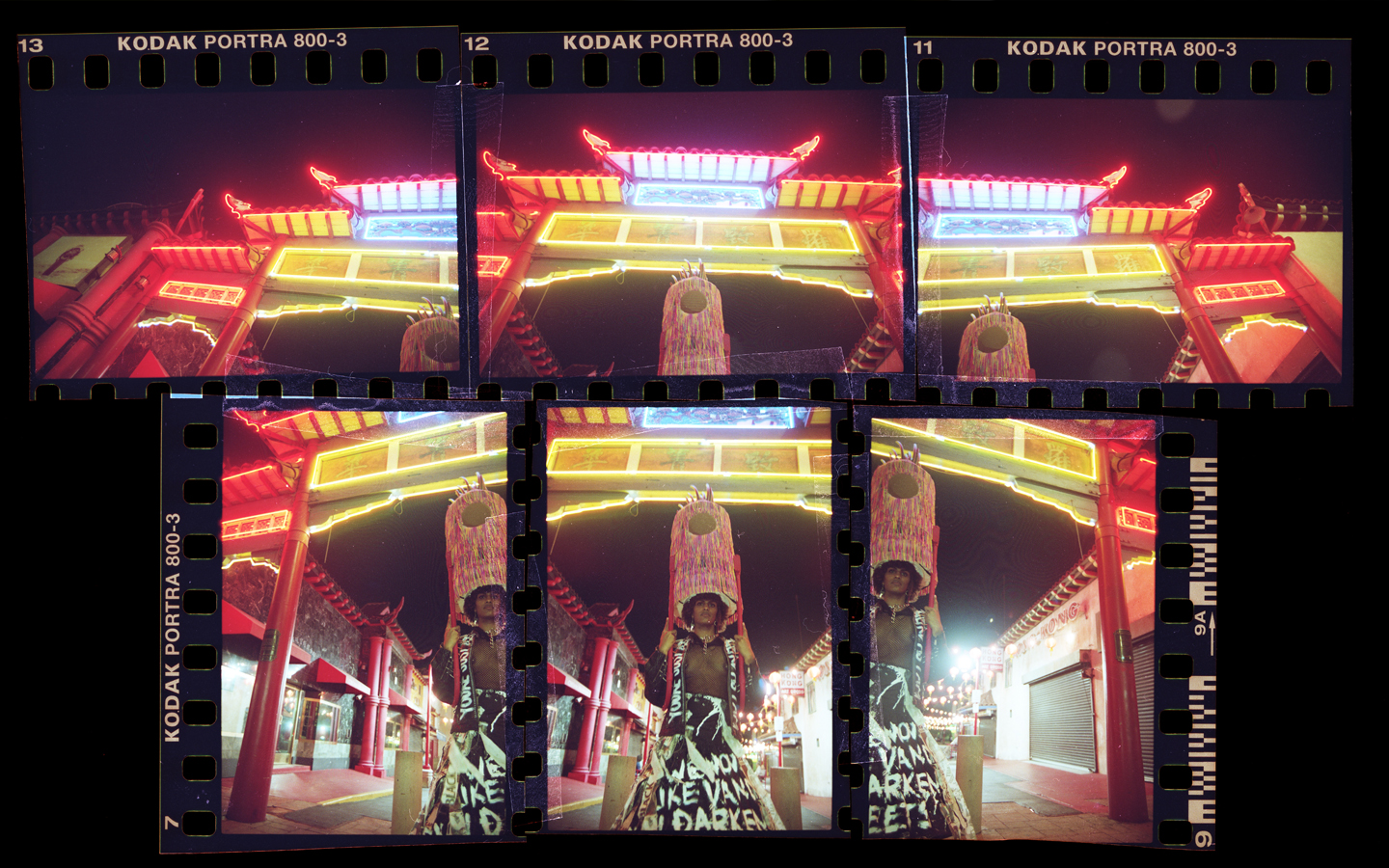

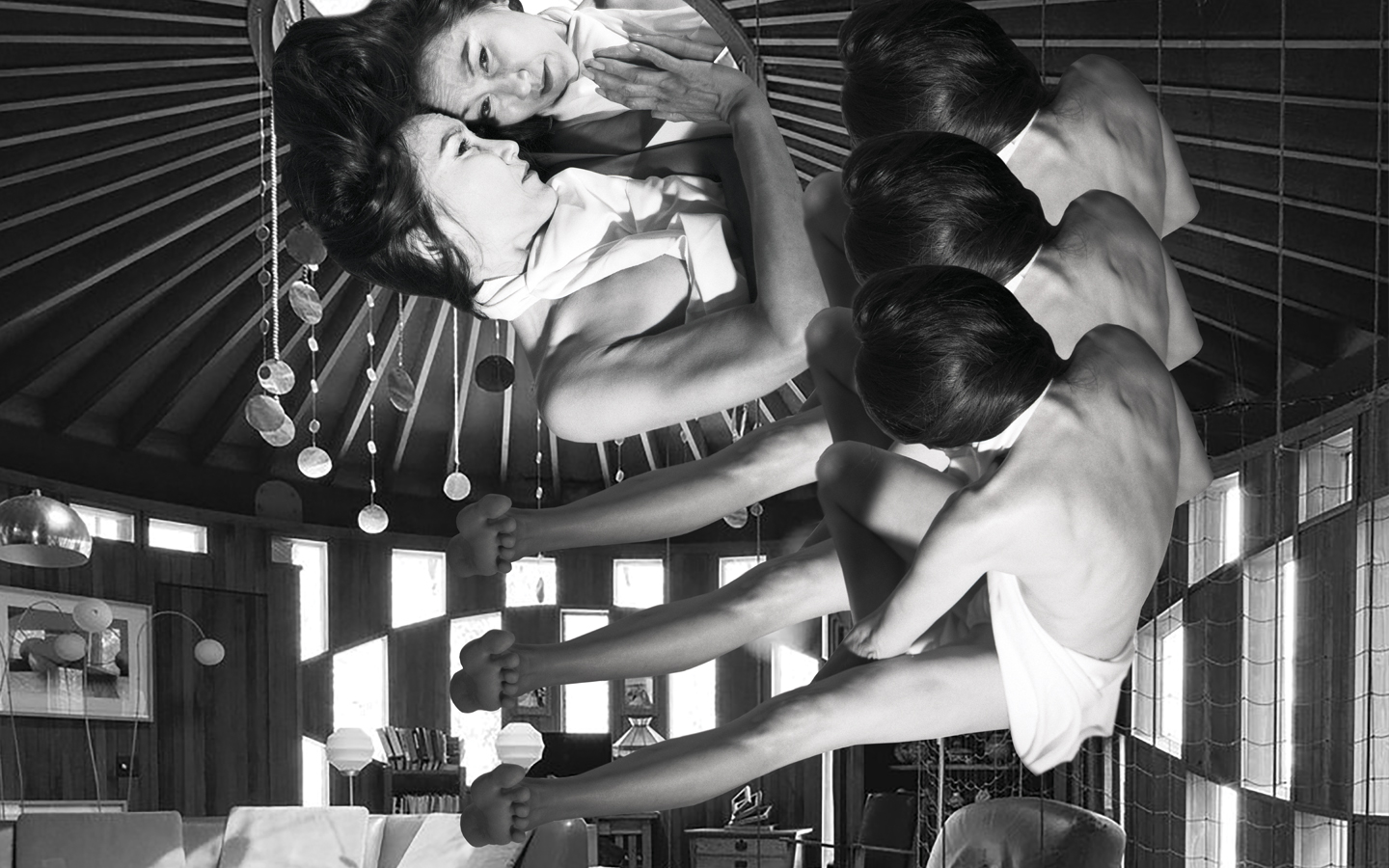

VISUAL KEMAL ÇILENGIR

A place is more than just coordinates on a map. Each location bears the imprints of history and is shaped by the stories that unfolded there. Walk the corridors of an abandoned building or settle into an old armchair and let imagination take over.

Walk down 19th Avenue, along the Los Angeles River, and the Lincoln Heights Jail looms. Built in 1927 during the peak of the Art Deco movement in Los Angeles, the city was filled with sweeping visions of modernism and progress. But ultra-modern exteriors like that of the Lincoln Heights Jail hid less-than-progressive ideas.

Though designed to hold a maximum of 625 occupants, at the height of its use, this jail held up to 2,800 prisoners—and was famous for overcrowding. Like most prisons today, the population at the Lincoln Heights Jail was disproportionately made up of minorities. The stories of their lives and the memories they shared in the jail add rich layers to the building. As with many people on the periphery of mainstream society, the stories of people who pass through the Lincoln Heights Jail tend not to be well-documented. The rich history, social hierarchy, and cultural dynamics that thrived inside its walls are mainly held in the memories of its inhabitants rather than in history books or official documents.

One of the most well-documented incidents connected to the jail is known as “Bloody Christmas,” an episode of police brutality aimed at the Mexican American community. While most of Los Angeles was celebrating the holiday or enjoying a few days off work, seven young Mexican Americans were suffering abuse at the hands of Los Angeles Police officers. As reported in the Los Angeles Times, the atmosphere was jovial as LAPD officers celebrated at the downtown police station.

Two officers then responded to a call at a nearby bar where Daniel Rodela and six friends were enjoying beers. LAPD was called to the scene to remove a few customers when a fight broke out among bar patrons and the officers. The seven revelers were later arrested at their homes; Rodela was beaten in front of his family for allegedly resisting arrest. All seven men were booked at the Lincoln Heights Jail where they endured beatings from multiple officers, according to an article published in the Los Angeles Times. For 95 minutes, the officers relentlessly beat the seven men until their cries echoed off the walls and blood covered the wooden walls and floor of the jail. Rodela suffered broken facial bones, countless other injuries, and required two blood transfusions in order to recover from this discriminatory violence. There is little information about how his six companions fared.

During the trial, the prosecuting attorney referred to the arrested men as “mad dogs” and “hoodlums,” a testament to the prevailing attitudes of the time. Relations between the Mexican American, or Chicano, community and law enforcement officers were especially taut during the 1950s. The Chicano community was subjected to random searches, unannounced raids on their homes and businesses, and undue police scrutiny. “It is becoming more and more difficult to walk through the streets of Los Angeles – and look Mexican!” lamented Ralph Guzmán in Eastside Sun, a local newspaper, in January 1954.

A report published by SurveyLA: The Los Angeles Historic Resources Survey cited this event as a key moment that helped set the stage for the Chicano movement. Also called “El Movimento,” this grassroots movement came to prominence in the 1960s and encouraged political engagement, community organizing, and honoring traditional arts.

Unfortunately, Mexican Americans weren’t the only group to face unfair persecution by the LAPD. It’s impossible to touch on the history of the Lincoln Heights Jail without acknowledging the role it played in LGBTQ history. As LGBTQ historian Lillian Faderman noted, all non-conforming, non-heterosexual prisoners were referred to as “gay” during the time that the jail was operational. “‘Gay’ was the umbrella term for all of us back then,” Faderman said in a phone interview. Members of the LGBTQ community were picked up on false charges and booked for exaggerated crimes such as cross-dressing or public indecency. Even women walking down the street in jeans, loose-cut tops, boots, and short hairstyles could be subjected to police harassment.

In the book Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians, authors Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons describe the realities of life for gay people in the city, from the early Native American days to the recent past. Faderman says that Lincoln Heights Jail was a popular holding place for many gay men who were picked up from the cruising scene at Pershing Square and for women who were arrested at lesbian bars on Vermont and 8th. The downtown cruising scene was an open secret for people in the gay community who were looking to explore their sexuality and connect with like-minded people. “In the 40s, 50s, and even the 60s, the police were really terrible to the gay community. Anything that wasn’t deemed ‘normal’ was upsetting to them,” said Faderman.

One prisoner, local barber Nancy Valverde, was routinely arrested for “masquerading” (dressing in a masculine style) and thrown in the “Big Daddy Tank” in the Lincoln Heights Jail. As she described in Gay L.A., Valverde was arrested almost every weekend for fifteen years and held at the Lincoln Heights Jail for a few nights at a time for her “crimes”—wearing clothing she bought off the rack at local shops and keeping her hair short. Despite these frequent encounters with the police, Valverde unapologetically continued to wear the clothes of her choosing and continued to pursue her career as a barber.

In 1959, Valverde looked up her rights in the Los Angeles Law Library and found that courts decided women could not be arrested for wearing men’s clothes. Although this ended her almost weekly arrests, it was not the end of harassment. Local police patrolling the area where she had her barbershop would routinely pester customers and intimidate clients, according to her account in Gay L.A.

While Valverde’s story seems outrageous by today’s standards, hers is one of the countless untold tales of gay prisoners who spent time in the Lincoln Heights Jail. As with many places on the darker side of history, most of the stories from inside the jail exist in an oral tradition, and records of daily life in the “Fruit Tank” are as ephemeral as the ghosts who undoubtedly haunt the cell walls.

After City Council closed the jail in 1965, it became the home for the Bilingual Foundation of the Arts from 1979 to 2014. This nonprofit stages productions of Spanish language and culturally relevant plays for the local community. The Foundation is currently located on North Los Angeles Street, near Little Tokyo.

During its time as a mixed-use building, tenants reported unsettling occurrences like water hoses turning on and off by themselves and the sound of chanting voices echoing off the walls. In 1994, a local boxing champion, Johnnie Flores, fell to his death in the elevator shaft after leaving the Los Angeles Youth Athletic Club. The community champion and amateur boxer was found at the bottom of the service elevator shaft just steps away from the boxing gym he founded and where he spent most of his days. This boxing gym made use of the former jail cells and holding tanks to provide athletic training for local youth. The L.A. Youth Athletic Club has since moved to West 7th Street.

Currently, the jail sits empty and has become a canvas for colorful splashes of graffiti and street art. Shuttered windows, barbed wire, and chain-link fences keep the curios away. Visible from the Metro Gold Line and across the Los Angeles River, this building has lost its purpose.

A redevelopment plan, selected by City Council in 2017, will transform this historic landmark into a mixed-use space. Lincoln Property Company and the Fifteen Group propose rebranding the jail a Lincoln Heights Makers District, which would include commercial and manufacturing spaces, a public market, creative office space, live-work housing, green space with an amphitheater, and a communal rooftop space. This trendy redevelopment makes no mention of how it will honor the historic significance of the space nor to what extent it will change the appearance of the building. Luckily, the building was named a Historic-Cultural Landmark in 1993, and the Los Angeles Conservancy and dedicated historians are safeguarding the stories housed within the jail. While its future may be uncertain, the past of the Lincoln Heights Jail remains fixed—yet somewhat elusive.